News

Robert de Vries writes for The Conversation on his Sutton Trust research on academy chains.

Nearly 15 years after the first academies – state-funded schools with more autonomy – were introduced in England, there is still relatively little information about how the reforms have affected children.

Now, new research has shown how some of the most disadvantaged children studying at academies that are part of larger school chains have seen their grades go up slightly more than the national average. But other academy chains have not helped pull up grades – showing a big variation across the system.

Fast-moving reforms

It was in March 2000 that the Labour education secretary David Blunkett outlined his vision for “City Academies”. These were to be a “radical approach” for failing schools “in the most challenging areas”. These schools would be partnered with sponsor organisations like charities, businesses, or churches, who would help turn things around. They would also have freedoms denied to ordinary state schools, like the ability to change how they paid teachers, or to alter their curricula.

By the 2010 general election, there were 203 City Academies. Today, 57% of all English state secondary schools are academies. Thankfully, most were not failing schools. In fact, there are now two distinct types of academy. Sponsored academies reflect the original vision – mostly poorly performing schools, with sponsors to help them improve. Converter academies are the new type – mostly good schools that have chosen to convert to academy status to benefit from the new autonomies the law gives them.

Most (around 3,000) of the 4,000 or so academies in England are actually converters. But in terms of social mobility, it’s what’s happening in the 1,000 sponsored academies that’s most interesting. These are the schools, often serving disadvantaged communities, which are in the best position to improve the fortunes of many poorer children.

Many of these sponsored academies are now part of “academy chains” – groups of schools all under the supervision of the same sponsor. Some, like the Dixons Academy Trust, have just a few schools, often in a single area. Others, like the Academies Enterprise Trust (AET), contain dozens of schools educating many thousands of children. Around half of all academies (both sponsored and convertor) are now in a chain of some kind – so what happens in these chains clearly matters.

Performance of academy chains

A new report by the Sutton Trust called Chain Effects, that I helped research with Merryn Hutchings of London Metropolitan University and Becky Francis of King’s College London digs into the performance of these chains in detail. Specifically we were most interested in how they were performing for their poorest pupils.

We compared 31 of the longer-standing chains on how well disadvantaged pupils were doing in their exams at the age of 16. We concentrated specifically on sponsored academies and – to be fair to the chains – we only looked at schools that had been with the chain for at least three full academic years (2010-11 to 2012-13). This was so we were only looking at schools where the sponsors had enough time to make a difference.

We found that, on average, the sponsored academies in our group of chains performed reasonably well. In 2013, across the country’s mainstream state schools – including all regular state schools, academies and free schools – around 43% of pupils that the department for education defines as “disadvantaged” (students who have been eligible for free school meals at some point in the past six years) were getting five A star to C grades at age 16.

The average for the same students in our group of chains was actually a little better: 45%. We also found that scores for disadvantaged students in around half of our chains had improved faster from 2011 to 2013 than had the average for mainstream schools.

Some better than others

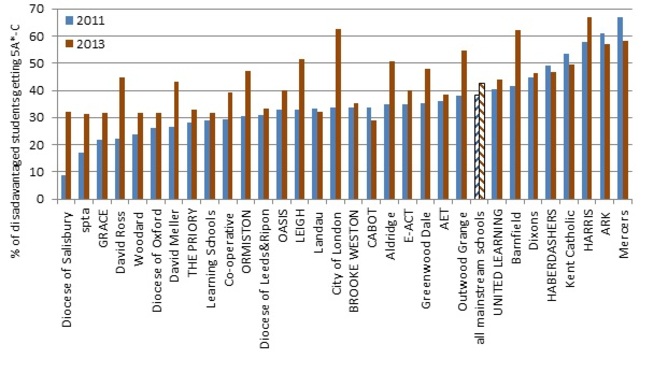

But there was a huge variation between the chains in terms of their performance. The graph below shows how each of our chains did in terms of the percentage of disadvantaged students getting five good grades in 2011 and 2013.

You can see that some chains, like David Ross, were performing below average in 2011, but have shown strong improvement. This is the pattern you might expect from sponsored academies: low early attainment followed by big improvements.

But you can also see that other chains, like Harris, have managed to achieve large improvements even though by 2011, they were starting from quite a high base. Unfortunately, the graph also shows that a number of chains started relatively low and have failed to improve, or have even fallen back.

Our research showed that this pattern is repeated across a number of different measures of exam performance. Some chains, like Harris and ARK do very well across the board; others do well in a few select areas, and others consistently underperform.

We know that different chains face different challenges. “Disadvantage” as defined by the department for education is quite broad and some chains will have a much more socio-economically deprived intake of pupils than others.

We also recognise that we’re only looking at exam performance – and that there are other important things about schools that this simply doesn’t capture. But given the huge effects academy chains can have on the future lives of their pupils, it’s important to look at these numbers. Some appear to be doing exactly what they’re supposed to – improving outcomes for disadvantaged children; others do not.

Our research is by no means the last word on this subject – it’s a starting point. This is why one of the most important recommendations we make is that the schools inspectorate Ofsted should be able to inspect academy chains as whole entities, just as they inspect individual schools. It’s best for everyone if parents, as well as politicians, can look at independent evaluations of these organisations – so they can make the best possible decisions for the children under their care.

See the article as it appeared on the Conversation here.