Opinion

Lee Elliot Major on the need for an evidence-based approach in the classroom

I have often thought that commentators who want to criticise teachers should first pass the ‘teacher test’ to earn the right to do so. Having spent time in front of an inner-city classroom (with a teacher beside me) I can tell you it is one of the most challenging (and rewarding) experiences I have ever had. And that was just for one hour!

We don’t value our teachers anywhere near enough. Few of us really understand (or could cope with) the demands of their job. Just ask Sir Peter Lampl, a hard-nosed business leader, who once thought teachers had it easy. After 15 years at the helm of the Sutton Trust he now talks only of admiration for the inspirational educators of our children.

But teachers remain vulnerable to one well-founded attack. Can they call themselves a true modern-day profession? I’m afraid not. And one of the main reasons is this. Teachers have yet to embrace an evidence-based approach to their work: there is no accepted body of knowledge, based on robust research, to inform what they do (or don’t do); nor is there a culture of investigation to evaluate what works best in their particular school or classroom. The contrast with the modus operandi of medics could not be starker.

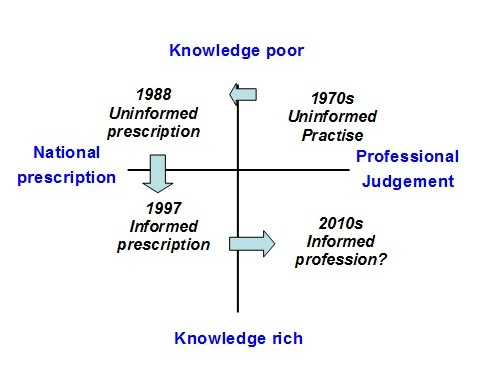

Below I have adapted a famous graph in education policy circles, first produced during New Labour’s early education reforms of the late 1990’s.

The graph describes the different phases of teaching during the last half century. It contrasts them in terms of the knowledge used to underpin the work of teachers, and the levels of autonomy they have enjoyed.

Before 1988 teachers were essentially practitioners free to pursue their own ways of working, with little reference to the body of research on what worked best. Then came the Big Bang of Baker’s Government reforms – the league tables, inspections and the national curriculum – that prescribed exactly what was expected in the classroom. A decade later under New Labour, another wave of top-down programmes emerged – the national numeracy and literacy strategies. These initiatives were based at least in part on the evidence of their impact.

The last phase of the graph highlights what has yet to be realised: the promised land of teachers as informed autonomous professionals, and no longer in need of Government direction.

The good news is that an accessible summary of education research on what works to raise attainment is now available. Last week saw the re-launch of the Sutton Trust-Education Endowment Foundation Toolkit. This is latest generation of the guide updating the evidence first released two years ago. It challenges many of the assumptions among teachers – revealing the limited impact from reducing class sizes and the current deployment of teaching assistants. This is one important step in the journey towards a teaching profession that embraces evidence. But it is really only the start: everyone knows that exercise is good for them, but that doesn’t mean we all do it, does it?

I see at least three major challenges for the deep cultural reforms needed for teaching to evolve into the respected profession it should be.

The first is the glacial timescale for change. The improved education systems across the world required concerted leadership and efforts over several years. This is the “grind not the glamour” that the EEF’s chief executive, Kevan Collins, talks about.

The second is the danger of Whitehall’s heavy hand that can stifle rather than stimulate change. The long hard road to reform extends well beyond Whitehall fads (evidence based policy is currently back in vogue) and Parliamentary cycles.

No, this change will have to come from teachers themselves. It is striking that in all the reviews of the nations at the top of the global education rankings, the common watchwords are professionalism, professional development, evidence, and research.