Opinion

Headteacher Tom Sherrington explains what he learnt at this week’s Sutton Trust/Gates Foundation international teaching summit in Washington DC.

The Sutton Gates summit has been excellent. After three days in Washington, I’ve got a wealth of material and I’ve had the luxury of some flying time to think about the key ideas I’m taking home. An overarching take-away is the sense that engaging in professional dialogue with people from around the world is a massive privilege. There is enormous power in the exchange of ideas on a national and international scale and cross-phase; this has been a feast.

The summit was very successful in placing research evidence at the heart of the discourse. Rob Coe’s session was excellent, bringing his Sutton Trust paper on what makes great teaching to life with some interactive polling software and a great discussion. His slides are here. It’s well worth looking at those slides, the Sutton Trust report and some of the blogs written about it – as compiled by @mrocallaghan_edu. Rob Coe skilfully responded to people bravely seeking to defend learning styles and the accuracy of their teacher evaluations. He also suggested that, in seeking to ensure that students are sufficiently challenged, we could do a lot worse than simply asking them. Research suggests that seeking student views has more value than a bit of nebulous ‘student voice’; it can help us to do a better job as teachers.

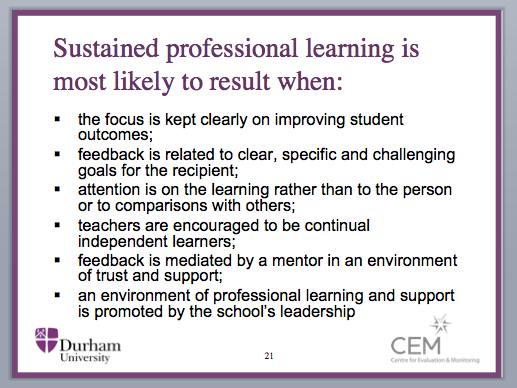

Perhaps the strongest take-away is the affirmation of a view I’ve held for a long while that professional learning for teachers and leaders is the single most important factor in transforming outcomes for learners (as opposed to the raft of accountability systems schools are bogged down with.) This is about developing a culture within which professional learning thrives – and developing practical tools. The two-pronged systems + culture approach needs to be considered explicitly and planned deliberately. This was reinforced by much of what Prof Coe presented and discussed:

Building the culture: some highlights

Trust: Paul Browning, a Principal from Australia, shared his ideas about trust, as described in a free ibook. It was a big hit – the talk of the summit. My take-away is the intention to think about developing trust explicitly, not simply by chance.

Developing a shared values statement – Teaching and Learning @HGS I presented a tool about building a shared, staff-owned agenda for teaching and learning and taking the time to do it. The feedback I received was hugely helpful and encouraged me to make sure we do this really well at Highbury Grove over the next year.

Rituals, language and environments We were encouraged to explore the idea of culture using a Harvard framework. I liked this. If you explore how a culture manifests itself in rituals, language and environments, it helps to plan how to change it. For example, if we ritually ask “How will we know if it works?”, we’ll be reinforcing the culture of enquiry and the search for evidence.

Physical and psychological space….This was another idea about culture. We need psychological space – time to reflect, plan, imagine, evaluate. If that’s always done on the fly, we’re less likely to succeed than if we set aside time for it. Leaders and teachers need time. Free time. Similarly, the physical space matters. Does the school building facilitate collaboration? One idea was to set-up collaborative project walls in a dedicated room that allow teachers to develop their thinking over time – all very California Google – but perhaps teachers would like that too.

Using audit tools– One of Rob Coe’s messages was to avoid the trap of assuming we do things already – without really testing it out. So, let’s not just assume we do things already and use some strong audit tools. I was plugging the NTEN Framework at every opportunity and a take-away was the Australian Educational Positioning System (EPS – geddit!). It looks well worth exploring in detail.

Putting the systems in place: some ideas

Managing time and workload: We discussed time a lot. It’s the key barrier to a lot of effective change. So where to find it? A number of practical solutions were floated:

- Routinely collapsing the school day every few weeks to give time for staff CPD and collaboration; using more staff training days.

- Over-staffing so that each teacher has more students in each class, but less teaching time, freeing time for peer observation and collaboration. The time vs class-size trade-off was discussed in some detail. Pupil premium?

- Appointing a specialist teacher to mentor colleagues and occasionally covering the lessons so they could undertake CPD activities.

- Replacing meetings with dedicated free time or collaboration time.

Tiered CPD- relative to career point: I saw two brilliant examples of this, one from a New Zealand Primary and one from Seven Kings in Ilford – their nicely titled ‘cradle to grave’ approach (it’s a metaphor!) . Both schools delivered a superbly structured package of CPD based on a personalised evaluation of each teacher’s needs, interests and career goals. I want this in my school.

Using assessment information to evaluate impact of specific approaches: This would be utterly obvious if it happened. But it doesn’t. For example, Rob Coe suggested that increasing ‘time on task’ is strongly linked to improving outcomes. (Go figure!). So why not measure time on task, try to increase it and see if that is happening and if outcomes improve. This kind of direct, focused impact analysis is probably worth way more than the endless array of wacky engagement stuff people get drawn into.

Feedback mechanisms eg coaching triads, lesson study, using video. There are lots of these things to try out and we should explore them. The key thing is to do so intelligently, knowing the limits of the process. We need to avoid the traps of focusing on teacher performance, assuming learning is happening or not happening without triangulating with student outcomes; we must give challenging and specific feedback. It’s easier to be a friend than to be critical as a critical friend.

Collaborative planning and assessment instead of meetings. I liked this a lot. A few delegates shared examples of teachers working together to plan learning tightly linked to specific learning outcomes and assessments. Instead of some of the usual department meetings, if teachers study test data to find key areas of strength and weakness (for themselves as well as their students), the process can inform better planning and better CPD with different teachers sharing their expertise.

Some other specific interesting ideas from primaries.

Co-teaching in Finland: This was very interesting. Across the school, pairs of teachers with parallel classes put their students together to teach them all collaboratively. The school found the impact was dramatic. The collaborative work, sharing of expertise, joint planning and analysis of assessments and scope for flexible groupings had a very big impact. Sometimes they’d teach them all in one large group but they could organise them in all kinds of groups for different modes of learning, whilst constantly learning from each other as partners.

Parental engagement in assessment and learning: Mutukaroa at Sylvia Park. NZ. The inspirational Headteacher Barbara Ala’alatoa explained how standards have risen dramatically by employing dedicated teachers to work one-to-one with families to discuss assessment information and to offer home-study support.

Organisational values and Mindsets: from NZ – Sarah Martin, Stonefields School. The school has a superbly articulated set of professional values that underpinned their work, including the need to be driven by evidence. ‘Informed next steps’; ‘Make learning visible’; Value the Voices’ – I love all of that, making the culture explicit and strongly orientated around learning.

Trivium 21st C as a basis for the HGS curriculum: Finally, I was hugely encouraged by the response in my Deep Dive workshop when I pitched the idea of using the Trivium 21st C (bringing together knowledge and skills) as a basis for a curriculum model – as advocated by Martin Robinson in his wonderful book. We discussed whether it would be possible to seed a staff-led process with the trivium model; giving staff scope to bring it to reality, leading – perhaps leading strongly – without dictating and still securing strong buy-in and ownership. We’ll see!

On the plane home, Sir Alasdair MacDonald, who co-ordinated the summit, interrupted my viewing of 22 Jump Street to hold a discussion about the key things we’d want politicians to do to support us. There are interesting parallels between the systems and culture we need at school level and the elements of an optimal national policy framework. A high trust culture isn’t just something we’d like; it’s essential to effect the changes we need. Until politicians wake up to the collective delusion of high-stakes accountability, we’ll always be shackled. At the same time we need support to develop leadership capacity, to guarantee ongoing professional learning for teachers and Heads and to disseminate well-researched tools. Government has a role to play in all of those areas.

Thanks again to the Sutton Trust and the Gates Foundation for giving us the opportunity to take part – and especially to Alasdair for asking me and for getting us all organised.

Tom Sherrington is headteacher of Highbury Grove school in London. He blogs at headguruteacher.com and tweets as @headguruteacher.