News

Laura Bruce, our Director of Programmes, reflects on the government’s review of university admissions and looks at how the use of predicted grades affected Sutton Trust students this year.

Post Qualification Admissions (PQA) and Post Qualification Offers (PQO) are policy ideas that have long been discussed and debated in higher education circles. With the government’s recent announcement into a consultation on the policy and the backing of Vice Chancellors and bodies such as UCAS and Universities UK, it appears that we are seeing for the first time the potential for actual exploration and implementation.

What does this mean in practice?

A shift away from the UK’s longstanding tradition of offering university applicants a “conditional” place based on their predicted grades, could see a process where applicants are given their offer after they receive the results of their examinations (PQO). An alternative move could go even further and see students applying to university only once they have their grades in hand and know which institutions match their grade profile (PQA).

The Sutton Trust have released research on this topic for a number of years, with our most recent student polling finding that disadvantaged students were less likely to get a place at their preferred university. Two thirds of students would be in favour of the move to PQA. Crucially, the polling highlighted that disadvantaged students, in particular, report that they would have applied to more selective universities had they known their exam results. This is a key argument for PQA, that disadvantaged students will be better armed to reach for the country’s leading universities.

What impact could PQA have?

It is challenging, however, to predict the full impact of predicted vs actual grades and how this may affect a student’s decision-making and behaviour, and indeed that of universities. By no means do we see PQA as a silver bullet for social mobility, but it does have its merits that we believe are worth exploring. As with all complex policy ideas, the devil will be in the detail and implementation of the policy.

For now, we want to understand students’ attitudes towards the proposed policy change and explore the impact that the current predicted grades system has on students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Previous research, conducted during more stable times, highlighted that high achieving disadvantaged students are more likely to have their grades underpredicted compared to their better off peers, which would support the PQA argument.

The pandemic highlighted problems with the current admissions system.

This year, however, put into sharp focus the use of predicted grades in university admissions through both the Centre Assessed Grades (CAGs), provided by a student’s school, and the government’s algorithm, which was billed as controlling for grade inflation and ensuring the system remained fair. Both of these methods demonstrate a process for predicting what a student’s attainment may have been in the absence of examination results.

We did see an overall increase in grades through CAGs, which led to the argument of over inflation of grades and the subsequent justification of standardisation. Very quickly, we also saw fears and evidence emerging that showed disadvantaged students were likely to be the most affected by the process of standardisation: the very process that was designed to make the grade allocation “fairer”. The government’s algorithm used a school’s historic performance to calculate the grades of individuals, which disproportionately brought down the grades of individuals who outperformed their circumstances.

This group are the ones targeted by Sutton Trust programmes: high achievers who show great potential but face barriers to accessing university and employment based on the school they attend, where they live or their family’s financial and educational background. We, therefore, wanted to understand how this year’s system affected our group of students and more broadly, build a picture of the potential impact of predicted grades on ‘outlier’ students who have the potential to outperform their circumstances.

It is important that we emphasise here that highlighting disparities in predicted vs actual grades is not a criticism of individual teachers and their efforts to support individual students. What we are highlighting here is that it is the system of prediction that is an inexact science.

How did this year’s admissions crisis affect Sutton Trust students?

To explore this, we sent a survey to c. 3000 Sutton Trust programme alumni who had the opportunity to enrol at university this September. We received 515 responses, representing roughly 20% of the cohort. Whilst not a predetermined statistically representative sample, the respondents mapped onto the spread of the wider group in terms of gender, socio-economic markers met and attainment, which means they are likely to paint a picture that is broadly representative of the wider Sutton Trust cohort.

A slightly smaller proportion of our students have gone on to university this year.

In terms of destination, we saw a slightly lower rate of university admissions for our students this year,compared with previous years.

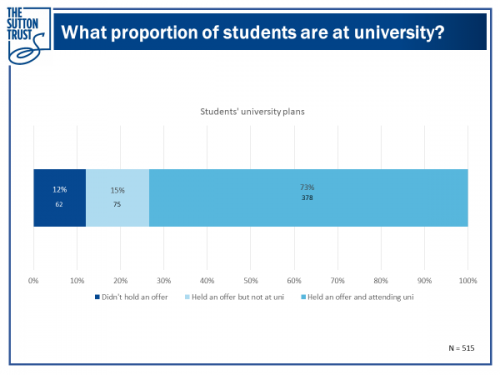

Figure 1: showing the proportion of Sutton Trust students who enrolled at university this September

Previous evaluations provided by the Institute for Employment Studies, showed an average enrolment rate for Sutton Trust students to university in the first HE ready year of 80%, rising to 93%+ when looking at admissions in the 3-year period following HE readiness. For this cohort, the survey indicates an enrolment rate of 73% for survey respondents, which is slightly lower for first HE ready year enrolments. We will receive the full administrative data set in April 2021 to give us a fuller picture.

Responses also indicated a similar distribution in terms of which universities our students have enrolled at, with 67% of those at university going to a leading university and 7% to Oxbridge, which is in line with our historic data sets.

It seems, therefore, that overall the use of CAGs to offer university places led to a slight decrease in university enrolments for Sutton Trust students but it has not significantly disadvantaged our group of students in terms of which universities they attended. This assertion must be taken in the context though that many universities chose to “honour the offer” made to students regardless of the grades they received through the CAG and government algorithm system. This affected 9% of our students whose CAGs did not meet their offer but were accepted into the university anyway.

If the algorithm grades had not been abandoned and universities did not “honour the offer”we would have likely seen big differences in the enrolment rates of Sutton Trust students at university this year.

High-attaining, lower income students were negatively affected by the algorithm.

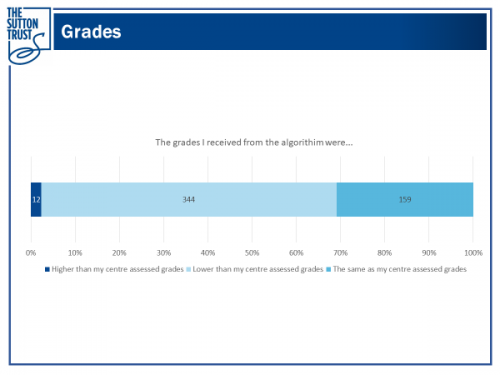

Our survey showed that two thirds of Sutton Trust students had their CAGs lowered through the government’s algorithm, and furthermore 25% of those that had their grades lowered had them lowered by 3 grades or more. This is significantly more than the rates reported for all students in both England and Scotland.

Figure 2: graph showing how students’ grades were affected by the algorithm

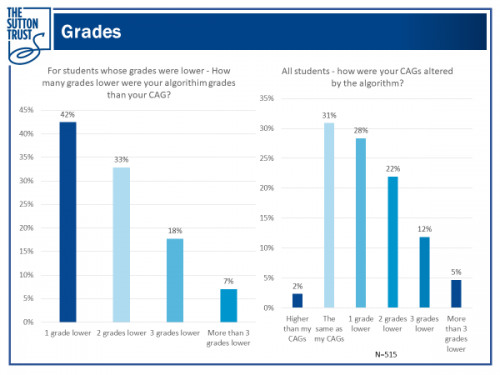

Figure 3: graphs showing the extent to which students’ grades were affected by the algorithm

That amounts to almost 1 in 5 of the overall Sutton Trust cohort having their A-levels reduced by 3 or more grades. Most concerning, is that our survey showed that it was students in receipt of free school meals who were the most likely to have their grades downgraded and most likely to have them reduced significantly.

The impact on enrolments rates had the government not returned to CAGs is unknown, and we are pleased that, despite the stressful experience and confusion for many students, that the enrolment rates for our students have stayed broadly similar.

6% of our students, however, told us that they lost their place at university in the period between algorithm release and the decision to revert to CAGs. For some students it was simply too late; despite their CAGs meeting their offer conditions, their offer had already been withdrawn. The majority of these students are looking to reapply to university again next year.

How do young people feel about university?

Beyond exploring grades and the impact on access, we also surveyed our students on their current attitudes to university. We know that access is the first step towards social mobility but what happens once students get there affects their success and eventual employment outcomes and so it is important that we are considering these factors, too.

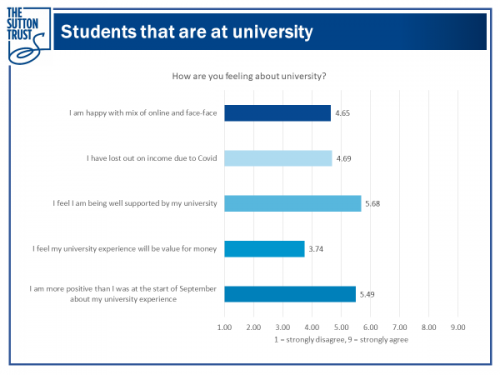

Figure 4: graph showing student’s attitudes towards their university experience

Our findings from these questions show that:

- two thirds of students do not think that their university experience will be value for money

- one third are less positive about university than they were at the start of September (this survey was conducted at the end of September), and

- almost a third are not happy with the support they are receiving from their institution

Furthermore, 41% of our students have identified that they have lost income due to COVID-19 and with many of our students relying on part time work and income to support their studies, there is a concern on financial viability for our students this year.

These statistics are concerning and are starker than we were anticipating. Since undertaking the survey, we have also seen an increase in student protests and complaints related to their current university experience. Our concern now is that although the enrolment rates for our students have stayed relatively stable this year, it looks like there is an increased chance of dissatisfaction with the university experience, a reduction in the perceived support available and that this could lead to increased dropout or could impact future outcomes for our students.

There has been evidence that this year is the best year for access to universities and this should be celebrated. We know historically that when the number of places at university increases, access increases. The lifting of the number cap allowed for more places this year, and universities stepped up to meet the challenge of predicted grades to honour the offer.

What next?

The question now is how we ensure that this year remains a success in terms of continued student participation amidst the challenges and disruption that students are facing. We also need to consider how we capture the lessons learned from the admissions process this year and university flexibility to ensure this isn’t a one-off year for access improvement.

An exploration of PQA is one avenue to explore to ensure that we can make substantial change to our systems for the benefit of social mobility and we look forward to contributing to the discussions and consultation.