News

Our new research outlines the amount of pressure students are under amid the cost of living crisis. Our Senior Research & Policy Manager, Rebecca Montacute, discusses the findings in more detail.

University students are known for living on a tight budget, favouring the classic beans on toast for dinner to keep costs down. But given the tight margins that constrain many students even in good times, the impact of the ongoing cost-of-living crisis on this group is of particular concern. This is especially true for those from poorer homes, who are less likely to be able to rely on their families for financial support.

In new research released on 26 January, we have surveyed over 1,000 current undergraduate students via the polling organisation Savanta, to better understand the impact the crisis is having on students.

The findings are deeply concerning, with some students having to take extreme measures, including skipping meals, to make ends meet.

How are students being affected?

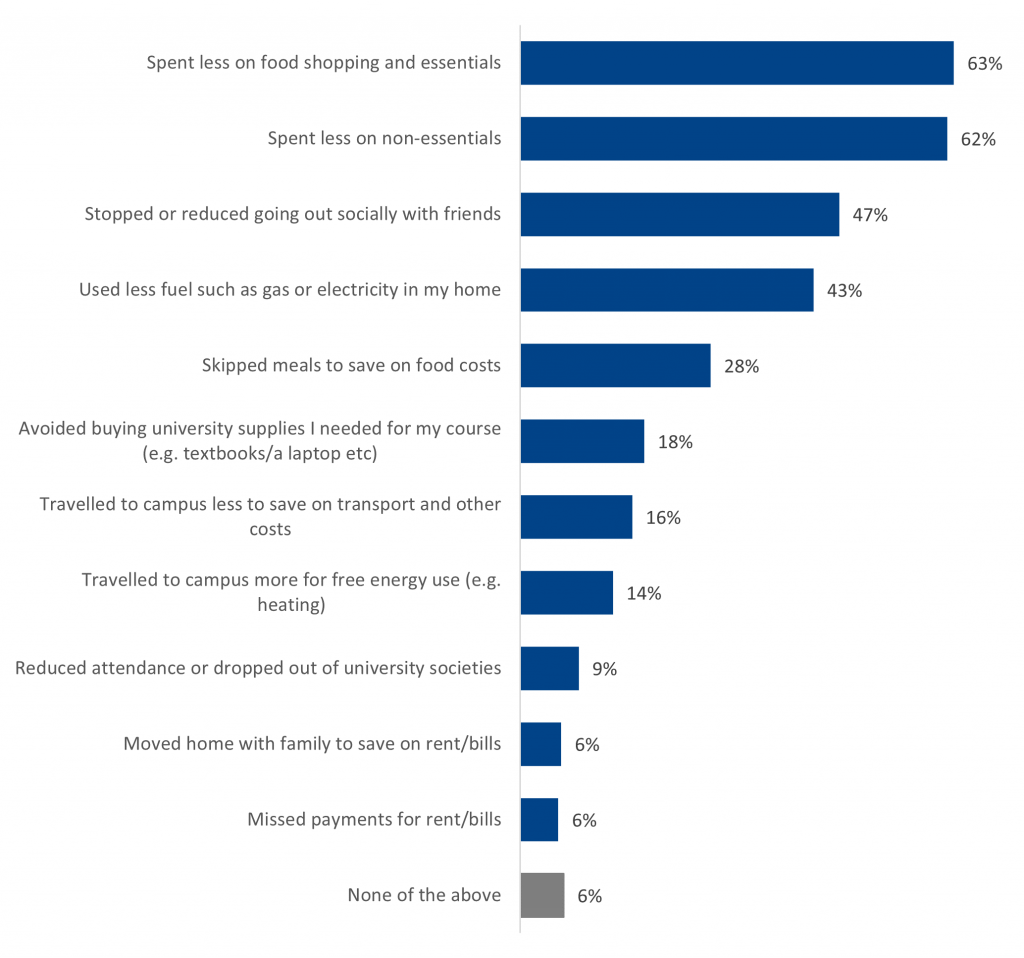

Since the start of the autumn term (September 2022), 63 per cent of the students we surveyed spent less on food and essentials, with 28 per cent saying they had skipped meals to save on food costs.

Just under half (43 per cent) said they had used less fuel such as electricity or gas in their homes, 47 per cent had stopped or reduced going out socially with friends and 6 per cent reported moving back in with their family to save money on rent or bills.

Over half (62 per cent) said they spent less on non-essentials and 18 per cent avoided buying university supplies they needed for their course, for example laptops or textbooks. Almost 1 in 10 (9 per cent) had reduced their attendance or dropped out of student societies.

Figure 1: How the cost-of-living crisis is impacting students

Which of these, if any, have you done this academic year (since September 2022) because of increases in the cost of living?

Uneven impacts

The impacts are also not being felt evenly. Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds were more likely to report skipping meals to save on food costs (33 per cent for those from working class families, compared to 24 per cent of middle-class students), and moving home with family to save on rent or bills (10 per cent compared to 4 per cent).

Looking at students in their second year and above, 57 per cent said their financial situation was worse this academic year compared to the year before, with 16 per cent describing the situation as much worse. The proportion saying it had worsened overall was higher for students from working class (66 per cent) than middle class (54 per cent) families.

Where are students going for support?

In the face of these financial concerns, many students have been turning to their parents (45 per cent) and or other family members (10 per cent) for additional financial support.

However, this is not an option for many students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, with lower proportions of working-class students receiving additional support from their parents (38 per cent compared to 48 per cent of those from better off families), or other family members (9 per cent compared to 12 per cent).

“Particularly concerning is that 4 per cent of students surveyed have taken on additional private loans.”

As well as family support, students are also finding other ways to help them make ends meet. Just over a quarter (27 per cent) had taken up a job or taken on additional hours and 11 per cent have received support such as hardship funds from their university. Of particular concern, 4 per cent of those we surveyed had taken on additional private loans, and 2 per cent had used a food bank or other charity support.

Government support

The “Energy Support Scheme” has been one of the key elements of support from government for households during the cost-of-living crisis. The scheme should have given every household in England, Wales and Scotland £400 to help with energy costs, paid to individuals via their energy company.

If someone’s landlord received this payment from their energy company (either as their rent is all-inclusive of bills, or because their landlord sells energy on to them from the energy company) they should have passed this £400 on to the individual’s household – including for students.

However, 40 per cent of students surveyed here living in private rental accommodation in eligible areas said they had not received this payment from either their landlord or their energy company, with a further 8 per cent unsure of whether they had received the payment or not. It appears that this core government support is not getting to many of the students who need it.

There is a significant risk that the crisis could end up impacting young people’s drop-out rates from higher education, as students struggle to make ends meet. Here, we found just under a quarter (24 per cent) of students said they were less likely to finish their degree due to the crisis, with 4 per cent saying they were much less likely.

What should be done?

Given the findings, it’s extremely disappointing that the government in England are only increasing maintenance loans by 2.8 per cent next academic year, when inflation is currently around 10 per cent. In Wales, the increase is much more generous, with the Welsh government recently confirming loans there will increase by 9.4 per cent – far closer to the level needed to meet the current increase in the cost of living.

In England, the government has also recently announced an additional £15 million will be available for universities to use for hardship funds. This is alongside an existing £261 million which government says universities can use for hardship funds, although as pointed out by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, much of this funding is already earmarked for other purposes.

“No young person should be unable to afford food or think about dropping out of their course due to a lack of funds.”

While the additional £15 million is welcome, if it were split between undergraduate students in England from the most deprived areas, it would equate to only £67 per student. Given the scale of the issues found in our polling of young people, this is clearly not enough to tackle the financial issues students are currently facing. While we strongly encourage universities to make as much funding as possible available for hardship funds, they are likely to be limited in what they can provide without additional support from government.

It’s clear that students need more money available day-to-day to make ends meet. No young person should be unable to afford food or think about dropping out of their course due to a lack of funds. And students shouldn’t be missing out on core parts of the university experience, like student societies, due to financial concerns. Longer term, the government should also look to re-introduce maintenance grants for less advantaged students.

Students deserve better, and government needs to ensure all students, no matter their financial position or family background, have an equal chance to succeed at university.

This piece was originally posted on the London School of Economics British Politics and Policy blog.