News

Professor Dave O’Brien is a globally recognised expert on the cultural and creative industries. As one of the authors of our research on social mobility and the creative industries, he unpacks the lack of fair access to creative higher education courses in the UK.

Creative Higher Education (HE) offers the promise of transformative experiences for students who are keen to pursue their passions and dreams. Passions and dreams are not exclusive to those from middle class backgrounds. Talent is everywhere, with over 150,000 students on creative courses every year. Opportunity, particularly at the most prestigious institutions, is not.

There is a crisis for social mobility in Creative HE. Our new report, A Class Act, with the Sutton Trust, builds on previous work with the Creative Diversity APPG, taking a deep dive into the question of who goes onto creative courses. The report tells a worrying story about the lack of access to elite institutions for students from working-class backgrounds and the dominance of these institutions by students from better-off starting points.

The report shows how, on the surface, proportions of students from working class and upper middle class backgrounds in creative HE look similar to the rest of HE as a whole. If we look at the type of school- private or state- students attend before university, there is greater access to creative HE for state school students than in HE more generally.

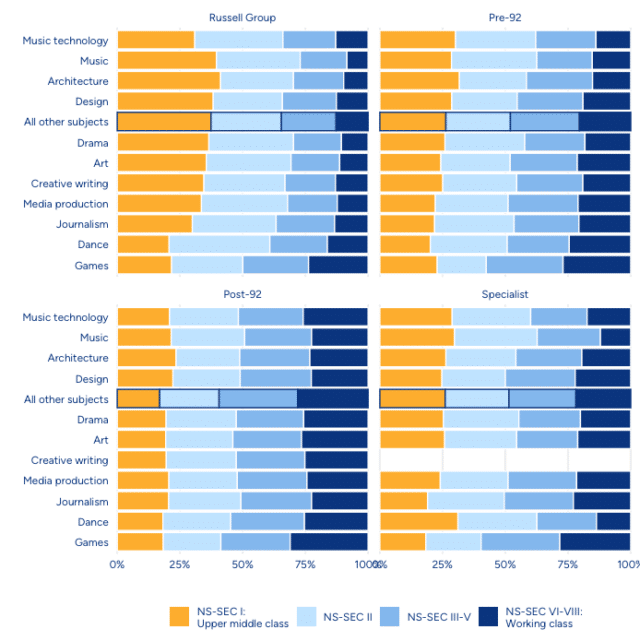

However, these headline figures hide considerable differences. There are differences between subjects, particularly between traditional arts subjects such as music and more modern creative subjects such as games. There are also important differences between groups of universities, such as the Russell Group and Post-92 universities (shown in the chart below), and between individual universities within these groups.

Creative subject groups and institution type by class background

At four institutions – Oxford and Cambridge, and King’s College London (Russell Group) and Bath (Pre-92) – more than half of creative students come from upper-middle-class backgrounds. Oxbridge (4% Cambridge, 5% Oxford) and older universities (Bath 4%, Bristol 5%, Manchester 7%) have the lowest proportions of creative students from working-class backgrounds.

Royal Academy of Music (60%), Royal College of Music (56%), Durham (48%), Kings College London (46%) and Bath (42%) all have very high proportions of privately educated students.

There are very low proportions of ethnic minority men and women in Art, Music and Drama, irrespective of their social class background. This is not the case for HE overall. Clearly creative HE subjects have an ethnicity, as much as a class, crisis.

Some of these inequalities are straightforward to explain. For example, the collapse of access to music teaching in state schools, following the previous government’s reforms to the school curriculum and the associated decline of in and out of school funding, undoubtedly plays a significant role in the dominance of private schools and upper- middle-class students on music courses.

It is an extremely difficult time for HE to have these conversations about access. The funding model is broken, with the combination of funds received through fees and direct support for creative courses not covering the cost of those courses. Creative courses are seeing staff cuts and closures. In some cases, the institutions under most pressure are the ones who have done the most to deliver access for working class students.

At a time of huge financial pressure for HE in the UK, institutions may be tempted to avoid the pressing need for equality of access. Yet creative HE will struggle to attract support if it continues to be exclusive. Outreach activities from the arts higher education sector (including conservatoires and other specialist arts institutions, as well as universities offering creative arts subjects) should focus on reaching young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Such activities should start early, to inspire children and ensure they can develop their skills over a long period of time.

The wider value of creative degrees should also be taken into account when making funding and policy decisions for the higher education sector. These courses do much more than just provide routes into creative work. Even if creative HE is only viewed through the lens of access to creative careers, inequalities in creative HE are a major reason why the creative sector has such catastrophically low levels of social mobility. As many as 69% of people in key creative occupations (such as actors, dancers, artists, writers) have a degree, compared to 26% of the entire workforce.

The crisis makes the need for a policy response even more important. Issues across the higher education system must not be an excuse for inaction. While there are explanations for the inequalities detailed in our analysis, there are few, if any justifications for the lack of diversity in creative higher education. If we want a more diverse set of creative industries, we need a more diverse creative HE.

Dave O’Brien is Professor of Cultural & Creative Industries at the University of Manchester.

The opinions of guest authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Sutton Trust.