Press Releases

Our Senior Research and Policy Manager, Rebecca Montacute, unpicks today’s polling.

After two sets of pandemic enforced school closures, and the associated disruption to children’s education, the government has been steadfast in their desire to avoid a third round. Just last week, the Education Secretary Nadhim Zahawi said “we must do everything in our power to keep all education and childcare settings open”.

And happily, unlike last winter, schools have both re-opened and remained opened this week. This is extremely welcome, given the impact previous rounds of closures have had, especially on the country’s poorest children.

However, there’s a danger that focusing on that fact alone misses the very real disruption that schools and their pupils have been facing this week. With extremely high rates of covid infection during the spread of the omicron variant, workplaces across the country are facing staffing issues, and schools are no exception.

Staff absences

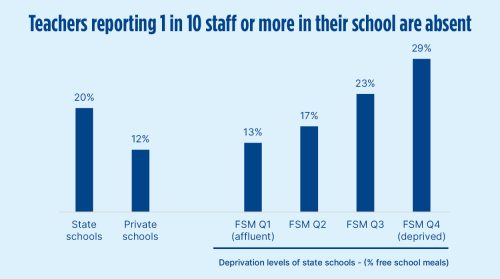

In our new research based on surveys carried out by Teacher Tapp, 20% of state school teachers reported 1 in 10 or more staff in their school are absent. This is higher than in private schools, where the figure is 12%. Of most concern, absences are also higher in the most deprived state schools, where this figure was 29%, compared to 13% in state schools with the most affluent intakes.

Figure 1: Teachers reporting 1 in 10 or more staff in their school are absent

The exact reason for these differences is unclear; with the cause likely to be a complex combination of many issues, including local infection rates, vaccination levels and the availability of testing to limit the spread of infection. However, yet again it seems to be the poorest young people who are facing the worst impacts of educational disruption during the pandemic.

Issues facing schools

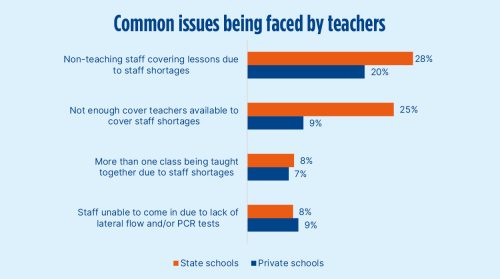

Staff absences and other impacts of the pandemic are currently posing several issues to schools. The most common issues cited by state school teachers include non-teaching staff having to cover lessons due to staff absences (28%), not having enough cover teachers to cover staff shortages (25%), and multiple classes being taught together (8%).

Classes being covered by non-teachers or large numbers of pupils being taught together is, of course, going to impact the quality of teaching available to pupils. And while this cover may keep children in classrooms, they are unlikely to be making the progress they could have made with their usual teacher or in their usual classes. And with many of these staffing issues more common in state than in private schools, the impacts are again unequal.

Another issue being faced by some teachers in availability of tests, with almost 1 in 10 state school teachers (8%) saying that staff at their school were unable to come in due to a lack of access to lateral flow or PCR tests. Improvements in testing capacity could help to keep more teachers in the classroom.

Figure 2: Common issues being faced by teachers as schools re-open

And while there haven’t been any large scale school closures, with high infection levels and many pupils still having to isolate, remote learning is still ongoing alongside face to face lessons. Our research has found a quarter of state school teachers have prepared materials for online learning in the last week, and earlier this week the online resource Oak National Academy reported its highest user figures since schools re-opened last spring.

However, while the picture on remote learning has improved since January 2021, many schools are still struggling to access devices for their pupils, with 29% of state school teachers reporting that more than 10% of their isolating pupils still don’t have access to devices for remote learning. This figure is even higher, at 48%, in the most deprived state schools. This is an issue that the government should have long since fixed, and the fact they haven’t done so is causing ongoing avoidable harm to students.

What next?

The government should be applauded for keeping schools open, and along with it avoiding the high levels of harm of further closures. But even with school gates kept open, pupils are still facing a large amount of disruption.

While the government have made some efforts to tackle staff shortages, including encouraging former teachers to return to the classroom, it has not been enough to avoid widespread disruption (perhaps unsurprising, given fewer than 600 people have signed up). Each of those teachers returning to the classroom will make a real difference to the schools they go to, but it is not enough to meet the scale of the challenge schools are facing. And given the high levels of infection in the community, issues caused by staff absences could continue for some time.

The government needs to look at urgent action to tackle this, including ensuring adequate funding is given to schools to pay for cover staff. Schools supporting the most disadvantaged young people, where absence rates are highest, should not be further penalised by the financial stress of bringing in additional support staff.

This ongoing disruption also re-enforces the urgent need for a real education recovery package for schools, at a level sufficient to meet the huge scale of disruption. The Sutton Trust, alongside many others, has previously warned the existing package is simply not enough to meet the level of disruption to learning.

And with exams still due to take place this year, but yet more disruption for the students due to sit them, it is also vital that the colleges, universities and employers making decisions on the basis of exam grades this year give extra consideration for those who have suffered the greatest impacts of the pandemic, for example by contextualising offers to take the impacts of the pandemic on attainment gaps into account.

Yet again, it is disadvantaged young people suffering the most disruption during the pandemic. While some of this has been unavoidable, there are further actions that government and others can take to minimise the impact and give this generation of young people the best chance of fulfilling their potential.