Alumni

As the general election approaches, the walls of Whitehall and beyond will no doubt be abuzz with discussions on immediate policy priorities, with researchers and policymakers alike sharing their top priorities for change. Indeed, later this week sees the launch of the Early Education and Childcare Coalition’s manifesto to transform the sector in England.

The Sutton Trust is proud to be a member of the coalition, and the manifesto will set out plans to rescue and reform early education and childcare, guaranteeing access to sustainable and high-quality early years provision for all children.

Improving access to early years education must be a clear priority given that since the COVID-19 pandemic, the early years attainment gap between the most and least deprived children has widened further. But there remain questions over the plans of all parties in this area.

Early education entitlements

Since publishing our briefing on our priorities for the early years, debate surrounding early education entitlements has continued. The National Audit Office has recently assessed the planned expansion of funded early education and childcare hours (15 hours for those aged nine months to three years for eligible working parents, then 30 hours for those aged nine months to school age), finding that only a third of local authorities are confident they will have enough places in September.

Indeed, in our briefing, we stressed the importance of staggering the rollout of any expansion of places, so that providers have time to successfully deliver high-quality additional places. We also raised that the plans will not reach many disadvantaged families, further widening inequalities in access.

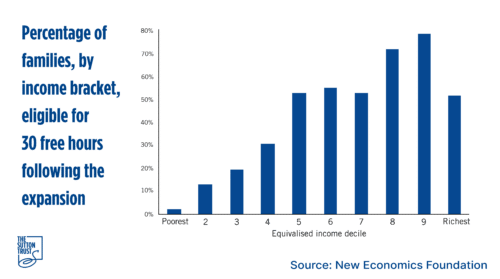

Evaluations from the New Economics Foundation looked at the likely distributional impact of the new entitlements by income level, from 9 months to 4 years of age. They too found very few poorer households will have access to the expansion, and a clear income distribution in access to early years entitlements, with better-off families benefitting the most (as shown in the chart below).

We have long made the case for expansion of the 30 funded hours policy for three- and four-year-olds to disadvantaged children, as the existing system in England provides less time in early education and care to the children from low-income families who stand to benefit the most: just 20% of families in the bottom third of the earnings distribution are currently eligible for the 30 hour entitlement. This inequality will be exacerbated by the new expansion plans.

A core entitlement of at least 20 hours per week (evidence states there are clear benefits to attainment and development from accessing early years settings for 20 hours) for all children, irrespective of their family’s working status or income level, would deliver for these families and stem the growth of the early years attainment gap. Where provision beyond this core educational entitlement is necessary for childcare purposes, additional hours should be affordable for all families, for example through a sliding scale of fees by income level.

To make sure any expansion of funded childcare delivers high-quality places, all those in the sector must be able to recruit a skilled workforce – in 2023, 1 in 5 early years staff members were unqualified (did not have a relevant GCSE/level 2 qualification), up from 1 in 7 in 2018. A new early years workforce strategy is urgently needed, with minimum qualification levels specified (for example, making level 3 a benchmark qualification), alongside adequate funding for settings to offer the higher wages needed to attract qualified staff, and to support training.

Delivery of such a strategy should be backed up by improved funding available to early years providers, particularly to support disadvantaged intakes, including through the early years pupil premium and the Early Years National Funding Formula. This is essential for any expansion of early education and childcare entitlements to be successful.

Access to children’s centres

Other important aspects of early years provision have also hit the headlines in recent weeks. New research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) evaluating Sure Start centres underlined the positive impact of living near a sure start centre on the GCSE grades of children from low-income families. This adds to the growing body of evidence which has found benefits ranging from reduced hospitalisations and higher educational attainment later in life.

Now that more positive evidence has come to light, it is even more concerning that the number of such centres has declined. Over 1,400 Sure Start Children’s centres have closed since 2010, with funding for these services also declining. The Sutton Trust wants to see improved high quality, community based early years support through children’s centres in the most disadvantaged areas, whether that be Sure Start centres or a similar model. A new strategy is needed for this provision that is coherent, sustained and national in scale, to reverse the decline and fragmentation of family services in the last two decades.

There is currently both political and public interest in the early years like never before. The next government has a huge chance to reshape the early years system in England for generations of children to come, with major implications for closing the attainment gap, improving the wider education system, and growing the economy in the long-run. We hope they get it right.