Alumni

How should higher education be improved post-pandemic? What do Sutton Trust alums think?

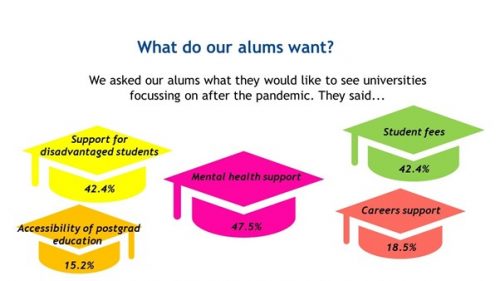

We’re delighted that our alums have put together the first ever Sutton Trust Alumni Policy Wishlist for what universities should prioritise in a post-pandemic world. Here are the top 5 priorities:

- Proper funding of maintenance grants for disadvantaged students.

- Access and funding for postgraduate studies for disadvantaged students.

- Better networking opportunities and career development programmes for lower income students.

- Better and more inclusive use of contextual admissions for university applications.

- Improving accessibility for disabled students at universities.

They came to these conclusions following our Alumni Festival policy discussion and alumni snap-polling on attitudes towards higher education. Read about the full policy discussion, and see our full alumni snap-polling views, below.

Alumni Festival Policy Discussion

The policy discussion saw experts across higher education give their guidance on what should be the focus in HE for the coming years. After a brief introduction from the chair and Alumni Leadership Board member Josiah Senu, our three panellists – James Turner, Larissa Kennedy and Nick Hillman – introduced their policies.

First up was the Sutton Trust’s own CEO, James Turner, who had stepped in to replace Anne-Marie Canning of the Brilliant Club. James started his speech by saying that, he has initially approached the question of what he would change in higher education through a broad lens, aligning closely with what the Sutton Trust are working towards. He said that he would like to see a reform of the education system as a whole, with greater wraparound support for students from an early age, to ensure that inequality and its impacts had been addressed before pupils even set foot on campus – an idealistic and broad solution. However, he then went on to say that, in his own words, this approach was ‘a bit of a cop out’, and that, as much as those in attendance would like to see a long-term solution to educational inequality, this would hardly support students facing hardships now. So, his approach for a more short-term solution to inequality in HE was to suggest broadening the use of contextual admissions and making sure that all young people are allowed to proceed in education regardless of how poor their schooling experience was. A key part of this, James suggested was recognising that contextualising admissions was not a dumbing down or lowering of standards, but instead a recognition of potential, and an admission that diversity in classrooms and teaching is valuable in and of itself and would help to enrich institutions form the ground up.

Next came Larissa Kennedy, the President of the National Union of Students. Larissa outlined her plan to ‘grasp at the root’ of inequity in HE, something which she says the NUS is focussing on with particular intensity after the pandemic. Larissa started by saying that, according to recent surveys, financial issues are some of the main barriers facing students in HE, particularly due to coronavirus. She pointed out that, with 1 in 3 students cutting back on food shops due to lack of money, and 1 in 10 using foodbanks, clearly more financial support is needed for students. In her eyes, the best way to address this immediately would be through the reintroduction of maintenance grants which would not only address immediate financial concerns, but also would help alleviate anxiety and stress for students in what has been a critical year for student mental health. Her second approach for addressing inequality in HE was more systemic – to democratise higher education and put more power in the hands of students. She argued that this year has seen a huge uprising against the marketisation of higher education, with rent strikes, occupations and other collective action all demonstrating that students will no longer accept that they should be ‘passive consumers’ in HE. She closed with a rousing call for students to seize the opportunity to take ownership of their own education as, after all, students know best what they need from their universities.

Then we heard from Nick Hillman, the director of the Higher Education Policy Institute. Nick opened by saying that he was surprised to find himself in the position of the most radical panel member and went on to outline his plan for the reorganisation of higher education. Nick argued for attendees to forget about the ‘mechanics and bureaucracies’ of higher education, and instead to focus on the wider goal, saying that to truly democratise HE, we must set a ‘bold target of involvement’ in HE in the UK. Nick argued that, although we have finally hit Tony Blair’s target of 50% inclusion at universities, it has taken far too long to get there, and, whilst a significant amount of the population has never attended – and therefore never benefited from – university, public funding will remain an unpopular option. By increasing the number of students attending HE to 75% of young people by 2035, we could make higher education into a universal service that benefits nearly everyone, and which would then qualify for greater funding due to its near universality. He then went on to outline why he believed that, at least for now, university fees should stay. He pointed out that, in all countries with free higher education, places in HE are capped, meaning that attendance is never truly democratic. Instead, the middle and upper classes will always dominate any limited system, meaning that participation for those from lower income backgrounds will remain low. The alternative, he argued, was to create as much educational opportunity as possible, and to make it as universal as possible. The way he saw it, only once the entire population believed that higher education was not just accessible, but beneficial for them and their children, could a properly funded public higher education system come into play.

It was at this point that alumni fed into the discussion. James was quizzed on whether he felt that all university courses were valuable, which Larissa pointed out stemmed from the marketisation of higher education in the UK. Nick was also asked whether he felt that 75% of students would even want to attend university, to which he replied that at the current rate this seemed likely, especially when you consider the number of students who could take on vocational degrees or degree-level qualifications.

Our alumni put forward some of their own recommendations to the panel. Current student Daniel talked movingly about his own experience of accessibility issues at university, as well as the loneliness that had faced many students this year. Another student who hasn’t yet started university, Goose, spoke about wanting to see greater career opportunities and networking events, especially after so many options had been limited, or made online only, in the wake of the pandemic.

Ultimately, Larissa’s suggestion of improving and widening access to maintenance grants came out top as our alums’ most highly voted recommendation. This was followed by improving access and funding for postgraduate studies, better networking opportunities and career development programmes for lower income students, better and more inclusive use of contextual admissions for university applications, and improved accessibility for disabled students at universities. We are very grateful to our panellists for taking part, and to all of our alums who gave such excellent recommendations.

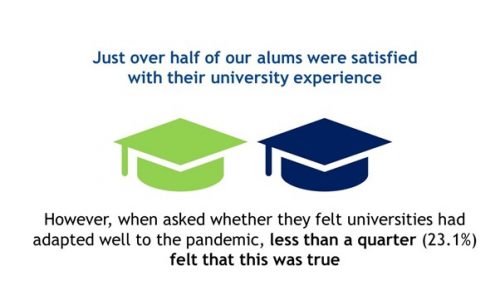

WHAT DO OUR ALUMNI THINK ABOUT HIGHER EDUCATION?