News

Who can become a top Olympian in Great Britain today? Can any young person with talent willing to put in the hard yards have a fair shot at Olympic success?

As the Paris Olympics comes to an end, we’ve looked at the backgrounds of Team GB athletes bringing home medals this week, to better understand the educational pathways they take enroute to the Olympic games.

How have we looked at Olympian’s backgrounds?

The school someone went to can give us a crucial insight into the social and economic circumstances they grew up in.

It’s not a perfect measure – but it is one which for most Olympian is relatively widely available, with private school attendance in particular strongly related to family income.

It should be noted that private school scholarships can be given to students who excel in a sport from a young age. For example, Tom Daley received scholarship offers from multiple private schools after the Beijing 2008 games, one of which he took up after experiencing bullying at his state school. Some private schools also open up their sports facilities for state school students to train, even if they don’t attend (such as Adam Peaty).

We’ve also looked at university attendance of top Olympians. Attendance at top universities is still highly socially selective, so this is another way to help us to better understand the socio-economic background and experiences of Olympians. Looking at university attendance also gives us a useful insight into the career pathways of top Olympians.

Team GB’s school attendance

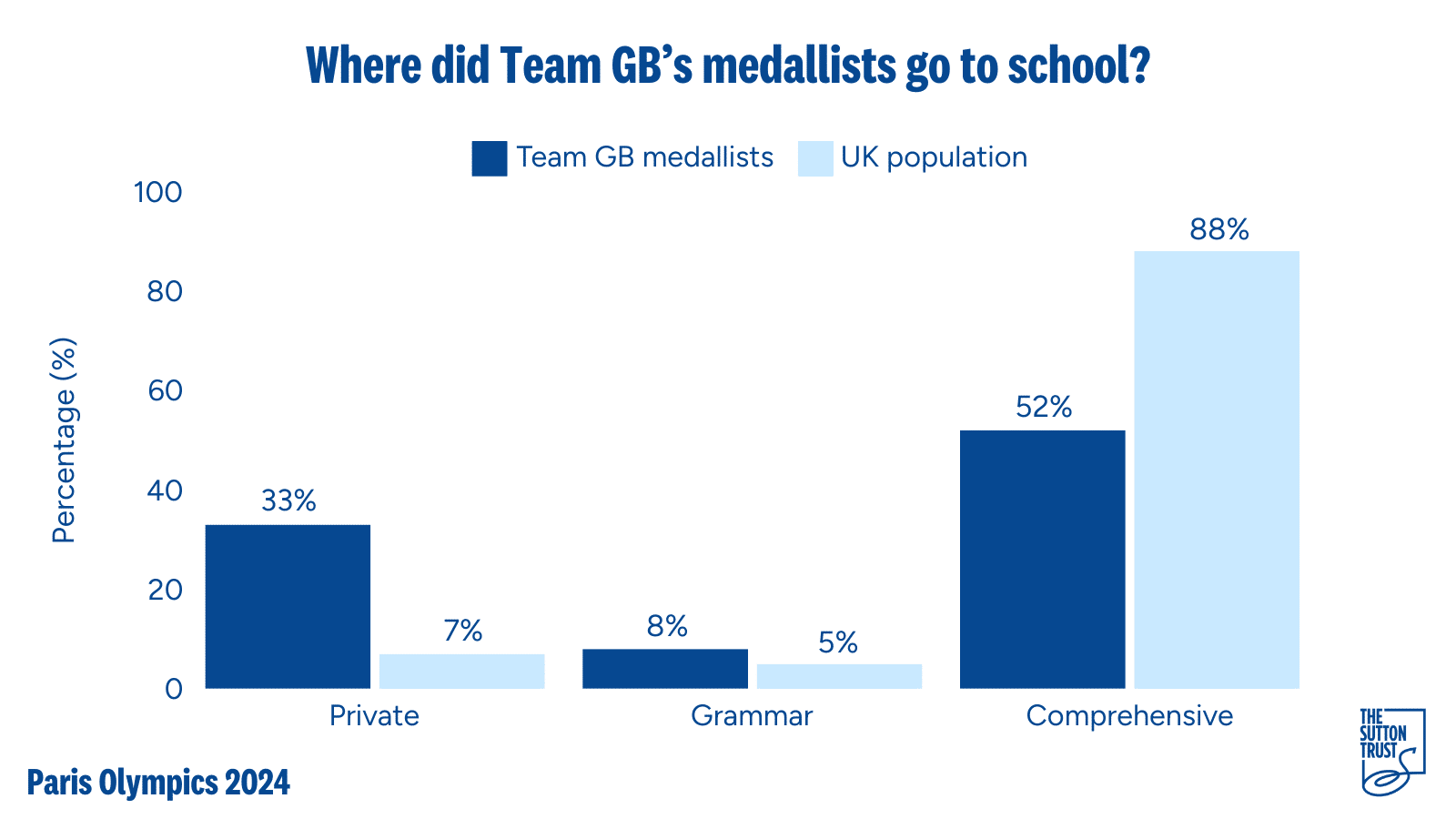

33% of medallists attended an independent school, making top Olympians over four times more likely to have been privately educated than the UK population overall (7%).

School type attended by Team GB medallists

Progress over time to increase the socio-economic diversity of top Olympians has not been linear. The proportion of privately educated medallists has gone up and down, 40% of medallists in 2021 (Tokyo) having been to an independent school, 31% in 2016 (Rio) and 36% in 2012 (London).

We classify the school someone attended by where they spent the majority of their time from 11-16. An even higher proportion of top Olympians (37%) went to a private school at some point in their education.

The proportion attending an independent school differs between sports, with medallists from rowing (57% of the 35 athletes with data available), swimming (50% of 8 athletes) and equestrian (38% of 8 athletes) the most likely to have attended. In contrast, all medallists with available data for canoeing, gymnastics, taekwondo, weightlifting, and boxing went to a comprehensive school.

Comparing to our previous analysis from 2019, the proportion of athletes who attended an independent school falls below the 43% of the England men’s cricket team who went to a private school, and just slightly below the 37% of the England men’s rugby team. But our top Olympians were considerably more likely to have attended private school than this summer’s men’s Euros football team (15%), and the women’s football World Cup squad in 2023 (0%).

University

60% of athletes attended university; 2% of which attended Oxbridge and 14% attended another Russell Group institution, compared to about 50% of young people going on to university by the age of 30 in the wider population. This is an increase from the 55% of medallists in 2021.

This is also quite different from other sports, for example none of England’s men’s 2024 Euro squad attended university. This is perhaps reflective of the high pay in men’s professional football, meaning they have less pressure to plan for future careers when they retire from the sport. In contrast, women’s footballers (where pay is generally much lower) are much more likely to have attended university than those in the men’s game (67% for the last tournament we have this data on). While many medallists can go on to high earnings from advertising and sponsorship, the pay for Olympians is relatively low, perhaps leading many to have one eye on their future career prospects and earning potential.

Universities can also give athletes access to high quality training facilities. For example, six medal winners at this games either train, study or studied at the University of Bath.

What might be impacting access?

Going back to the school attended by athletes, independent schools often heavily invest in their sports facilities.

For example, some independent schools, including Eton College, Abingdon School, Shrewsbury School and Radley College have their own rowing clubs. Millfield school has an Olympic sized swimming pool and students are coached by former Olympians. Stonar school has its own horse stables. Private school pupils also have access to 10x more green space than the average state school student.

Some state schools do offer high-standard facilities, particularly if they are linked to a local sports centre. But most often, private schools are in a different league when it comes to these facilities. And concerningly, Sutton Trust research has found budgets are increasingly strained in many schools, with 26% of senior leaders saying they have had to cut back on sports and other extracurricular activities, up from 15% in 2022.

These disparities are too often not spoken about. During the Paris Olympics, BBC Sports presenter Clare Balding made headlines after her on-screen surprise to hear that the Olympic Gold medallist Rebecca Adlington had not had any Olympians visit her state school growing up – again highlighting the differences in opportunities available.

And even if access to top facilities is not provided by their school, young people from wealthier backgrounds are much more likely to be able to afford access to sporting facilities outside of the school gates, through clubs or societies.

Changing access to sport

The London 2012 Olympic motto was to “Inspire a generation”, with the games aiming to increase participation in sport. 12 years on, we would expect to see the benefits of those games in the top athletes coming through in Paris. Yet the proportion of privately educated medallists has barely shifted in that time.

Change is needed at every level, from the allocation of sport funding, to actions taken by community sports clubs to widen access. Increasing funding for sporting facilities and equipment in state schools would be a significant step, and such facilities could be available to those outside of the school after school and in the holidays. Improving access would be beneficial not just for aspiring athletes, but also for those looking to boost their general fitness and wellbeing.

Looking at the Olympic pipeline specifically, UK Sport (funded by the UK Government and the National Lottery, and who provide much of the funding for Olympic sports and future potential medallists), should have a focus on improving socio-economic diversity for athletes coming through for LA 2028 and Brisbane 2032.

Highlighting these access gaps certainly does not take away from the amazing achievements of Team GB this summer. But this research should act as a reminder that, for all young people inspired by the summer’s sporting stars, we need a step change in access to sport going forward.

Data note: School data was available for 93% of athletes. University data was available for 98% of athletes.