Opinion

This blog is part of a series looking at challenges and opportunities in education as we come out of the pandemic, based on interviews with a range of experts carried out during 2021.

After experiencing prolonged periods away from the classroom during the pandemic, taking the jump into a new college, university or place of work may feel even more daunting than usual for today’s young people.

And these transition points have been made even more complicated by a changing landscape in post-16 provision, including an expansion of technical routes – with the introduction of T Levels to offer both classroom learning and workplace experience to 17 and 18 year olds. An increased recognition of the importance and value of apprenticeships and other technical routes has also continued.

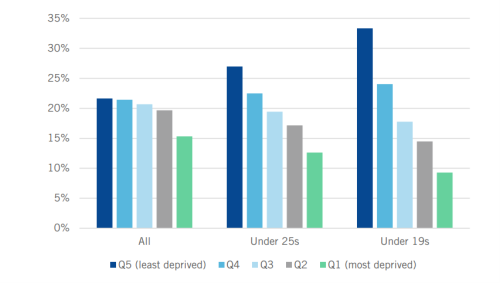

But further education is still too often not considered on an equal footing with higher education, and young people do not get equal information on both routes. Our recent research on careers guidance found year 13s are over 4 times more likely to receive significant guidance at school about university compared to apprenticeships (46% vs 10%) and even fewer are given information on further education or training routes (7%) (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of year 13 students who had received guidance about particular routes during their education

Our last blog in the Build Back Better series looked at ways to improve further and vocational education and training routes. Here, we’ll look at views from our experts on how best to support young people making decisions about these routes, including ways to simplify the landscape.

Choosing qualifications

One major barrier for vocational options post-16 is the huge number of different options on offer, creating a complex landscape for young people. The introduction of T levels, if done well, has the potential to add new high quality qualifications into the mix, but also risks further complicating a system which is already challenging to navigate.

Looking back at our interviews with our interviewees, whilst several were optimistic about the introduction of T-levels, the general consensus was that they will need time to become fully embedded into the education system. One interviewee was keen to see extensive evaluations of T levels, and if they were to fail, to see a new, more straightforward system brought in.

Some of our experts stressed it would be important to ensure T levels are not siloed, but seen alongside options such as traineeships and apprenticeships. One interviewee stressed that it will be crucial that government bring in higher education, which has not thus far had much involvement in the development of T levels, so that the qualifications are trusted and valued within that sector too. Indeed, it took a long period of time before BTECs started to be recognised in university admissions, which is still an ongoing issue – the government should learn lessons from that process, and do what it can to prevent the same problems for T levels.

“Opportunities are fragmented, we need a coherent system with quality information and guidance on what qualifications are and where they will get you”.

The experts we interviewed generally agreed that greater awareness of Level 4 and 5 qualifications was needed amongst students, parents, and employers. They felt these groups did not understand the content and pathways available to those completing Level 4s and 5s, compared to young people completing a traditional university degree. There were also concerns as to whether all sectors would accept qualifications at this level, for example accountancy was highlighted by an interviewee as an industry As with T levels, interviewees also highlighted the complexity of the Level 4 and 5 system, as it has a wide variety of different qualifications with varying structures, sizes, pricing and different quality measures. This in turn makes it harder for young people and their advisers to navigate.

The barrier of perceptions

But improving participation in FE and apprenticeships is not just about simplifying and improving the quality of routes on offer – perception is a major issue for the FE sector, with too many viewing A levels as the norm, and other routes as inferior in comparison. Many of our interviewees felt that FE, together with the early years, were not taken seriously enough by government or the media, with education policy too heavily focused on secondary schools and higher education.

Our experts stressed the need to bring the student voice to the forefront when looking to build positive perceptions of the sector, and that too often students are not asked enough about their experiences or what they want out of their education. An interviewee stressed the need for schools, colleges and policymakers to come together to allow students to speak about their experiences.

When it came to funding for improving access to FE, somewhat controversially, some interviewees were keen to see less spent on widening participation in HE, and for the money to instead be re-directed to FE. One interviewee thought widening participation funding had been spent on “building an army of people to spend it”, rather than really moving the dial on access in the last 10 years, and that the funding could be put to better use elsewhere.

Another of our experts said that part of the perception issue surrounding FE are the complexities of the system, which makes it difficult to understand. They also said that they felt government ministers would not send their own children to FE colleges, and that this was symptomatic of a sector which is not properly respected or valued.

Making a decision

Numerous schemes were introduced during the pandemic to increase places and encourage uptake in FE, like Kickstart, designed to boost youth unemployment, with additional funding available for training and support. But experts we spoke to were not entirely convinced; one interviewee for example thought that the different schemes were not well connected. For Kickstart and T-levels specifically, the expert wanted clearer information to be made available, to help both students and employers understand which option was right for them. Several interviewees were also concerned that confusion over the qualifications could result in students simply not choosing to do them.

“Post pandemic, a Youth Guarantee is needed. Efforts can’t be made up of lots of different initiatives, because young people will fall through the cracks.”

Those in the higher education sector felt that increasing both supply and demand in FE needs to go beyond existing schemes. There were concerns that HE is still considered as the best route by those who are middle-class, and that FE is not regarded as a worthwhile option. Some interviewees felt that greater flexibility between college and university routes, for example allowing people to do a year at college followed by two years at university, could help to open up access to a broader range of young people. Similarly, an interviewee suggested helping more people to undertake a Level 4 course or Higher National Diplomas (HNDs) could help to bridge the gap, allowing those with qualifications at lower levels to potentially progress to university .

Interviewees also raised areas for improvement when it comes to transitioning from FE into HE. Some interviewees felt that transitions into HE were not taken as seriously as other education transition points, and that there is not currently enough evidence on this area. One commented that much more support is needed for students before they arrive, for example through offer holder events, and that there also needed to be a focus on wellbeing.

Moving forward

No matter where young people are heading after they leave school or college, it is vital that education institutions and employers provide the correct support to a generation of young people negatively impacted by the pandemic. This support should not just be regarding the skills needed for a student’s new place of education or employment, but should also focus on mental health and wellbeing. Indeed, HEPI have recently recommended that universities should be cultivating a sense of community amongst students who have spent many months isolated from their peers.

At the Trust, post-16 transitions will be a key area covered by our Covid Social Mobility and Opportunities (COSMO) study, led with UCL and the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS). Responses from over 12,000 students will allow us to gain insights into the transitions of disadvantaged students into work and further education, as well has how the pandemic has impacted this crucial part of someone’s life.

As the post-16 landscape continues to change and grow, receiving impartial and high-quality guidance whilst at school is more important than ever. The Sutton Trust has recommended more investment in national information sources and programmes on technical education routes, to improve the advice available. Evidence also suggests that too many schools are not meeting their statutory requirements under the ‘Baker Clause’ – that all schools must allow colleges and FE training providers to speak to all students from year 8 upwards about technical qualifications and apprenticeships. The Trust has also recommended better enforcement of the clause, for example, looking at incentives such as limiting Ofsted grades in schools who do not comply with it.

As well as improved guidance, we have also long called for an increase in the supply of higher and degree-level apprenticeships, targeted at younger age groups rather than those already well into the workforce, to give young people a platform for progression to higher level learning and careers. Disadvantaged young people are substantially less likely than their better-off peers to take up the best apprenticeships, and for those who do choose an apprenticeship, they are more likely to be working in a low-quality setting with little career progression. More disadvantaged young people should be able to choose a degree apprenticeship, as they have the potential to be powerful vehicles for social mobility.

Decisions made at age 16 have huge implications for a young person’s future. We owe it to them to make sure the post-16 landscape has high quality options, valued by education institutions and employers, for students of all interests and aptitudes; and it is as straightforward as possible to navigate for today’s young people.

For more information, see our introductory blog, where you will also find links to the whole series.