Opinion

Schools and teachers in England are going through difficult times. The pandemic and its aftermath as well as the cost of living crisis have exacerbated already existing problems in education leading to record levels of pupil absence, increasing problems with pupil behaviour and ever more challenging teacher recruitment and retention. As outlined in our recent General Election policy briefing, they have also also led to a widening disadvantage attainment gap. Although the factors combining to create this almost perfect storm are multiple and complex, there is nonetheless a common thread that can be traced running between them that not only helps offer some understanding of the interrelatedness of the problems but also offer a glimpse of at least part of the solution. Linking these together is the recurring theme of poverty and hunger.

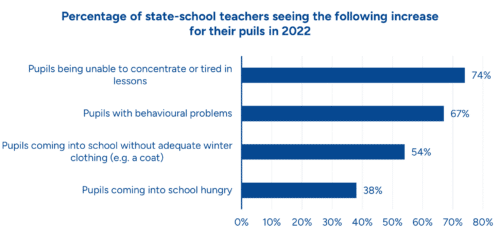

At the start of the cost of living crisis Sutton Trust polling found that 38% of state school teachers reported seeing increasing numbers of children coming into school hungry and 17% said they had seen an increase in families asking to be referred to foodbanks. At the same time – and likely to be related – 74% of teachers noted an increase in pupils unable to concentrate or tired in class, 67% said they had seen more students with behaviour issues. Indeed, the Trussell Trust, the UK’s largest food bank operator, supplied nearly 3 million emergency food parcels in the 12 months to March 2023, the most ever distributed by the network in a year and 37% more than in the previous year. In the following six months to September 2023 they distributed a further 1.5 million, up 16% on the same period in 2022.

Hunger in the classroom adversely affects pupil development and academic achievement. Hungry children struggle to concentrate, have low energy levels and are more likely to be involved in disruptive behaviour (which also affects others) and display higher levels of absenteeism. This all affects their academic progress and ability to learn.

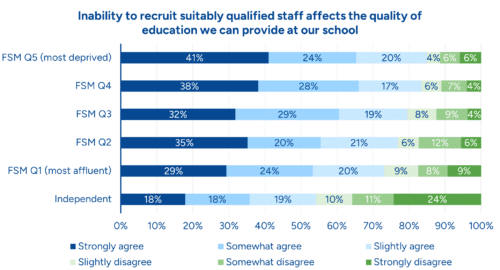

Teacher recruitment and retention is also related to poverty, hunger and the attainment gap. Sutton Trust research has found that schools serving disadvantaged communities experience greater recruitment difficulties, particularly in secondary schools. Teachers in the most disadvantaged secondary schools in 2019 were twice as likely to report that their department was not well-staffed with suitably qualified teachers (30% compared to 14% in the schools with the most affluent intakes) and 85% of teachers in disadvantaged schools reported that recruitment was affecting the quality of education their school was providing. This is partly because disadvantaged schools are seen by many teachers as more difficult to teach in. Behaviour can also be an issue here so schools with more disadvantaged and hungry pupils are likely to face more behavioural challenges.

Addressing hunger is not going to solve all of these problems, but it is clear that it will go some way to addressing at least some of them, freeing up schools to get on with teaching and learning.

The next government needs to put in place interventions to end hunger in schools. This is why the Sutton Trust has been calling for the expansion of free school meals entitlement to all pupils on universal credit and increasing breakfast club provision beyond the patchy cover currently on offer. Breakfast clubs have been shown to tackle hunger in schools and help poorer families with the costs of ensuring better nutrition for their children. This in turn can help improve concentration and preparedness for class, give children valuable social engagement before class and help lead to better class behaviour and attendance, ultimately leading to higher attainment. We should therefore welcome Labour plans to expand breakfast club provision to all primary schools and Liberal Democrat plans to extend free school meals to all children in poverty. The current income cap on free school meal eligibility excludes 1.7 million children in families eligible for universal credit from this benefit while such families are six times more likely to be classified as food insecure than ineligible families.

Child poverty is not the only challenge facing our schools and teachers, but what is clear is that until it is seriously tackled, and ideally eradicated, we will undoubtedly continue to see its impacts on education, particularly for the most disadvantaged. In the meantime, practical interventions like expanding FSM eligibility and breakfast clubs can at least go some way to minimising these impacts.