News

Nik Miller is the Chief Executive of the Bridge Group, and a co-author of our latest report, Bridging the Gap. Here he discusses what we can learn from the socio-economic diversity within the engineering profession.

Social equality in the professions

Over the last decade, we’ve been exploring how socio-economic background affects access and career progression in the professions, and how this contributes importantly to social mobility in the UK.

Building on our previous research together, last week we published with the Sutton Trust a new report that focused on professional roles in engineering. This sector is often celebrated as a beacon for social inclusion and mobility. The analysis reveals a profession from which many positive lessons can be learned, but where significant inequalities are still observed – especially relating to progression to senior roles.

Overall SEB diversity in the engineering profession

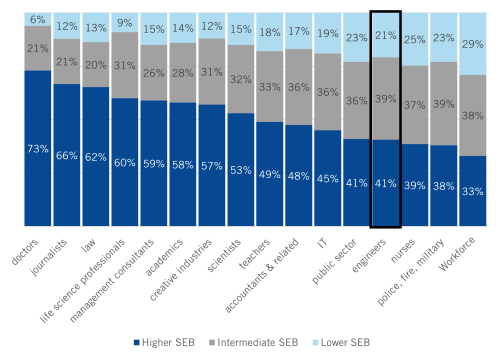

Harnessing evidence from national datasets, we highlight that people in professional roles in engineering are more diverse by socio-economic background (SEB) relative to most other comparable sectors. As illustrated below, 21% of those working professional jobs in engineering are from lower SEB, compared with 17% of accountants and 15% of management consultants.

However, these percentages all indicate low diversity compared with the wider workforce, where in this dataset 29% are from lower SEB.

Percentage of professionals by SEB and sector, Labour Force Survey

A range of factors contribute to this diversity in professional engineering roles, including: the geographical spread of roles; labour market demands; and individual perceptions of the profession. Each of these are explored in the full report, along with many other contributing factors.

The engineering workforce is complex and varied with respect to the roles undertaken; and it has been shaped by highly specific historical and geographical factors. Here, as in our wider work, we observe that workforce demographics are often a construct of tradition and history, as much as they are affected by specific recruitment or promotion practices.

Pay and progression gaps by SEB

However, while professional roles in engineering are relatively more diverse by SEB, the evidence highlights numerous issues in the talent pipeline that create barriers to entry and progression for those from lower SEB.

For example, the split between students taking ‘vocational’ and ‘academic’ routes into the profession risks creating a two-tier system, closely aligned with socio-economic divides. Students from lower SEB are more likely to take a vocational route, which confers fewer opportunities for progression; while those from higher SEB are more likely to take academic routes into the profession, which are typically higher status (and often better paid).

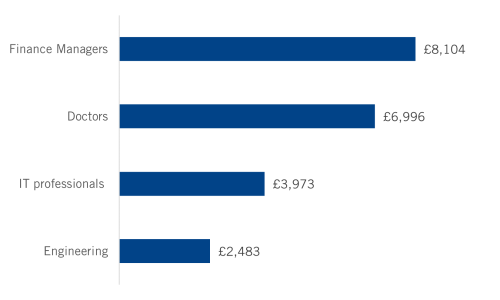

While the ‘class pay gap’ is smaller among professionals in engineering compared with most other professions, there remains a gap: those from higher SEBs earn on average £2,483 more per annum compared with those from other SEBs (when controlling for factors including occupational area, educational attainment, geography, gender and ethnicity). The same ‘class pay gap’ is higher in many other professions – for example among finance managers (£8,104), doctors (£6,996), and IT professionals (£3,973).

The ‘class pay gap’ in different sectors

There are several reasons why the ‘class pay gap’ may be less pronounced in engineering compared with other skilled professions, such as accountancy or law. In the latter, for example, knowledge can be relatively subjective, and this means it can be harder to measure performance on an objective basis. This tends to place more weight on softer skills, such as ‘polish’, ‘confidence’ and ‘gravitas’, which act as proxies for expertise, and which map to social class.

In contrast, engineering is a relatively technical area. On this basis it can be relatively meritocratic because performance is assessed in relation to more neutral measures of ability and effort. In addition, engineering has perhaps historically been fashioned as less cerebral or ‘gentlemanly’ than, for example, law or financial services. While these constructions are somewhat wide of the mark, as engineering is a highly skilled profession, its association with ‘hand’ rather than ‘head’ can cast a relatively long shadow, continuing to influence perceptions of who ‘fits’.

Further exploration of the evidence highlights that, within engineering, those from higher SEB are much more likely to progress to higher managerial and professional roles. In engineering almost three quarters (71%) of people in their thirties from higher SEB are in managerial or professional roles, compared with just 39% from lower SEB.

SEB and its relationship with gender and ethnicity

We find important intersections between SEB and other diversity characteristics, most notably gender and ethnicity – and our evidence indicates that a greater focus on SEB would also progress these other areas.

For example, considering gender, the progression gap is not only more pronounced in engineering compared with many other professional sectors, but is also amplified by SEB, which has a stronger effect on women’s progression compared to the effect on men’s.

The class progression gap is most marked in engineering for women who also identify as being from an ethnic background other than White. Those in this population from higher SEB are 70% more likely to hold a managerial or professional position, compared with the same group from lower SEB. This suggests that women from ethnically diverse backgrounds are less likely to progress to these positions and, if they do progress, they are much more likely to be from a higher SEB.

Engineering matters

Those working in the sector shape the world we live in, and how we interact with it. Engineers inform many of the ways in which our society is changing. Most of today’s services and products have a strong element of engineering, with people’s lives affected deeply by innovation, design, and manufacture. There is much for the professions to learn from engineering, but also actions that are needed within this sector to enable more equal progression.

As this year’s submissions are invited for the Social Mobility Index we’ve been reflecting on the noticeable lack of submissions from engineering firms to the last round, which was published in autumn 2021. Our hope is that this study will build the foundation for creating a renewed effort among engineering firms to focus on this topic – for reasons of equality and because of the business case for action. There is also, within the sector, a strong focus on gender equality, without much understanding about how this relates to SEB.

Practical actions

There are practical recommendations in the report for how the sector can progress its work in this area. This includes the more robust collection of data, consortium working, greater inclusion and progression routes to senior roles, understanding better the relationship between SEB and gender, and celebrating more loudly what is already effective, within and beyond the sector.

The Bridge Group, in partnership with the Sutton Trust, are planning an online event in April, at which we will bring together key people across the engineering sector to explore our findings and recommendations (Please contact [email protected] if you wish to be invited).

We will encourage organisations to partner with the Bridge Group to collect data, and with the Sutton Trust to build on their programme, Pathways to Engineering.

We hope our research together will inspire action at a time when the imperative for social equality is clear – and the role of our engineering sector more vital than ever.