Opinion

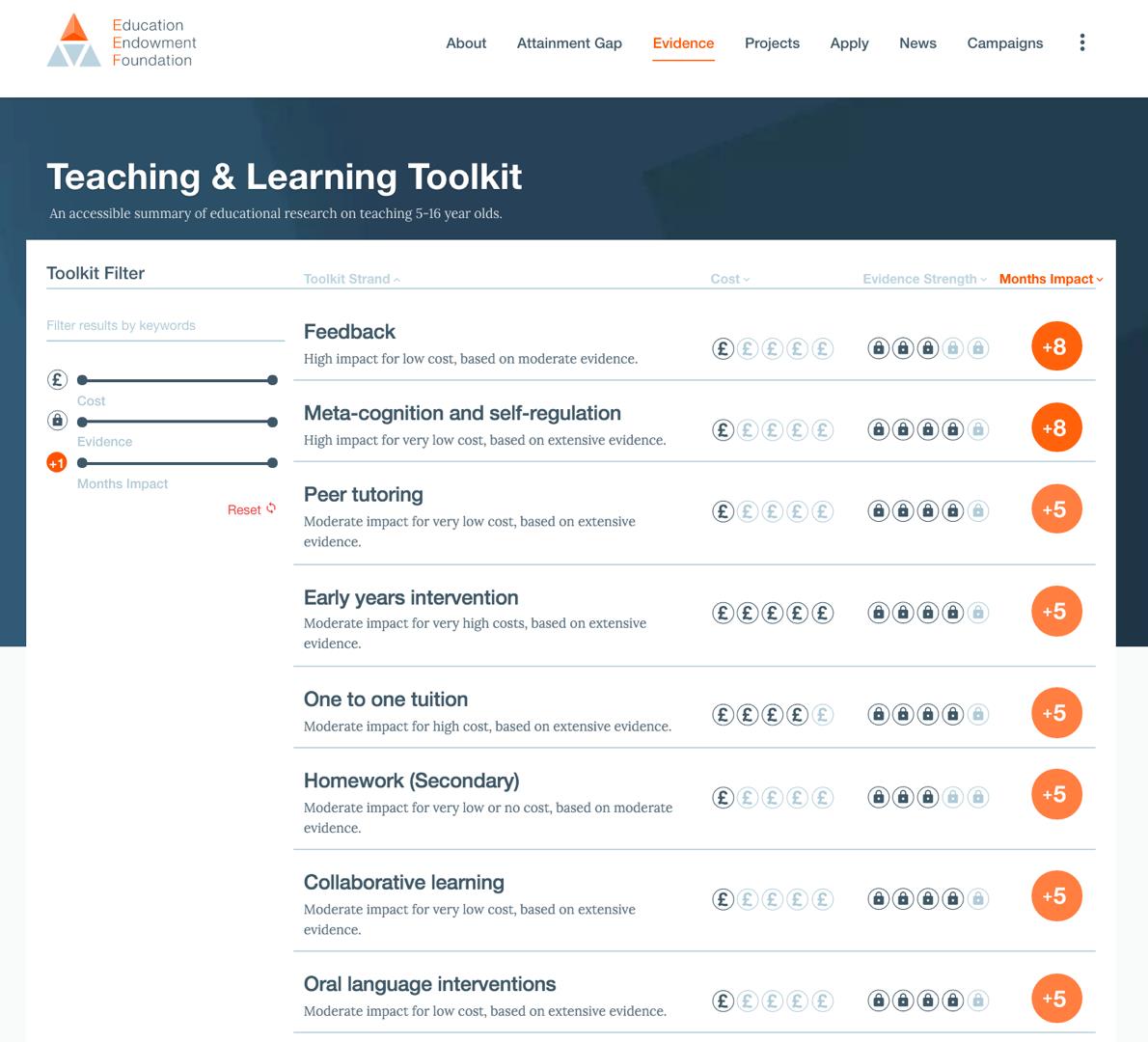

It was unveiled exactly five years ago today. Nine months in gestation, costing only £14,000 to produce, the Pupil Premium Toolkit started life as a 20-page report published by the Sutton Trust. There had been summaries of education research before. But what made our Toolkit different was its accessible ‘Which guide’ format designed specifically with busy heateachers in mind. ‘Best bets’ for improving children’s attainment were presented in the language teachers would immediately understand: the extra months of learning approaches might lead to during an academic year.

Its myth-busting messages immediately caused a stir: teaching assistants on average added little to pupil achievement; reducing class sizes had surprisingly limited impact; selecting by ability harmed the progress of the poorest pupils; different learning styles had no evidential basis whatsoever.

Yet the guidance chimed with what good teachers already knew from their practice. The things that really mattered were all down to the classroom interaction between teacher and pupil: providing and receiving effective feedback; ‘metacognitive‘ strategies making learning goals explicit; providing one-to-one (or indeed two-to-one or three-to-one) tuition for children falling behind their peers.

The Toolkit even came with its own guiding law. The ‘Bananarama principle’ states that “it’s not what you spend but the way you spend it, that’s what gets results”. Many teachers are now too young to get the cultural reference to the 1980s’ pop group who, with Fun Boy Three, covered this Ella Fitzgerald song. But we still believe that schools could do more to consider costs alongside the possible impact of the things they do.

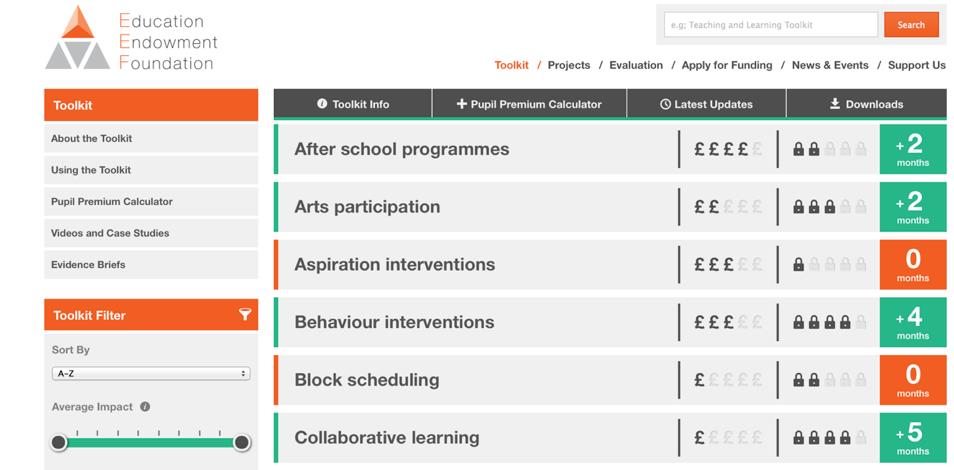

We wouldn’t have imagined in our wildest dreams how successful and widely read the Toolkit has become. Adopted by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) it became the Teaching and Learning Toolkit and has been further nurtured and developed into the 34-strand interactive website you see today. Two-thirds of school leaders say they use it, according to a recent independent survey by the National Audit Office. And hardly a day goes by when one of us doesn’t bump into a teacher who cites it.

It was lauded in Whitehall when the ‘What Works’ centres were established (although strictly we would prefer the less snappy title ‘what has worked’). Durham University has been praised for the impact this research project has had. It has even inspired a version in Australia, and an Early Years version has also been produced. Other countries are queuing up.

There is little doubt that the Toolkit has helped to create a more evidence-led culture in the classroom. Teachers ask questions about research now in a way they simply didn’t five years ago.

However evidence can be misinterpreted, misquoted, used and abused. We’ve been quietly bemused when two opposing sides of a major education policy debate have cited the same Toolkit strand to back their arguments. There is still a tendency for policy-based evidence rather than evidence-based policy. We have been very concerned to hear stories of schools sacking their teaching assistants when the Toolkit’s evidence suggests that better training and deployment are what is required.

The Toolkit may have also inadvertently added to the pressure on schools to focus on specific interventions and quick fixes rather than the most important challenge of all: improving the quality of teaching in the classroom. Our annual surveys of Pupil Premium use in schools for example reveal apparently little focus on developing effective feedback.

An ongoing challenge for the EEF is to develop the next evidence-led practical steps that take teachers from the general messages outlined in the Toolkit to the specific actions needed to improve the learning of their most disadvantaged pupils.

But the Toolkit came at the perfect time. It has shown that if you make evidence accessible, teachers will use it. Last week the Toolkit’s advisory group met up to discuss the next phases of improvements and development. It was a reminder that this guide will always be an ever changing, uncompleted piece of work, evolving with the latest education evidence. And that’s how we always envisioned it. The Toolkit has grown up and now has a life of its own.

Lee Elliot Major commissioned the first Toolkit and Steve Higgins was its original author.