Press Releases

Today we have published a new briefing ahead of the upcoming general election, looking at the gap in attainment between pupils from the most and least well off homes. Pupils finishing primary school in England last year were a third less likely to achieve the expected standards in reading, writing and maths if they came from a disadvantaged background. Year 11 pupils from lower socio-economic backgrounds were only half as likely to get grade 5 or above in English and maths GCSE compared to their wealthier peers. And the proportion of disadvantaged pupils studying A levels, just 14%, is only just over half of that at GCSE level.

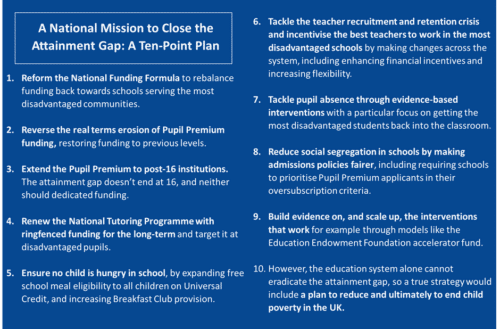

This is not about ability, but about inequality in access to high quality education. And the gap gets progressively wider as children go through the system (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The disadvantage gap at reception and the end of KS2 and KS4 in 2022. Source: Education Policy Institute

These figures reveal what is known as the attainment gap: the difference in educational outcomes between students from more and less affluent backgrounds.

Attainment is the biggest driver of gaps in university progression, and has knock-on implications for young people’s careers, and ultimately the chances of social mobility and higher earnings. The fact that so many disadvantaged young people are not fulfilling their potential also means that employers, businesses and the economy more generally are all missing out on wasted talent. This neglected talent could make a vital contribution to economic growth, a major aim for all major political parties.

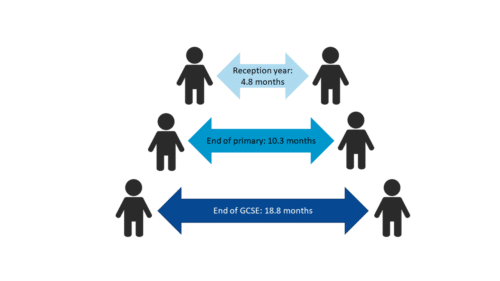

During the early 2010s, the gap across all school stages had been narrowing gradually. However, this progress stalled in 2017, before the pandemic altered the landscape considerably. Since 2020, the attainment gap has widened notably, with 10 years of progress in closing the gap wiped out in just a few years.

While there has been broad support across the political spectrum for efforts to reduce the gap, it has not been a major issue in political debate. But the issue is a ticking time bomb for future social mobility.

Figure 2: Disadvantage gap index at Key Stage 4. CAG = Centre assessment grades, TAG = Teacher assessment grades. Source: Department for Education

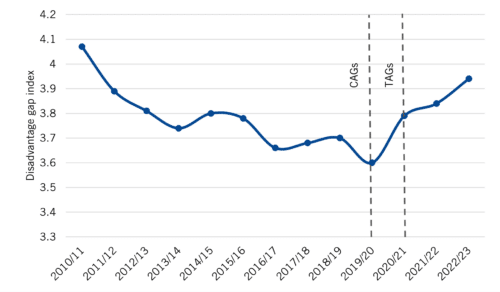

The Sutton Trust is calling for the next government to set out a long-term national strategy to close the attainment gap. Today’s briefing sets out a ten-point plan, to form a new national mission to close the gap for good.

This includes building on what has been shown to work, for example making a long-term commitment to funding a national in-school tutoring programme, like that set up during the pandemic. It includes reversing real terms cuts to key educational budgets targeting disadvantaged pupils in schools through the Pupil Premium, and reversing changes made to school funding in 2018 that disproportionately benefited schools in less deprived areas. And as family disadvantage does not disappear at age 16, Pupil Premium funding should also be extended to pupils at 16-19.

With pupil absences skyrocketing following the pandemic, the government needs to focus on getting the most disadvantaged pupils back into the classroom, including, potentially, more home visits, reducing the cost of schooling and broadening free school meal eligibility.

Closing the attainment gap also needs disadvantaged pupils to have access to the best possible teaching. Yet research has found that the teacher recruitment and retention crisis, an issue in schools across the country, disproportionately impacts schools and pupils in disadvantaged areas. The government needs to tackle this problem with, for instance, enhanced financial incentives for teachers to work in schools with high levels of deprivation.

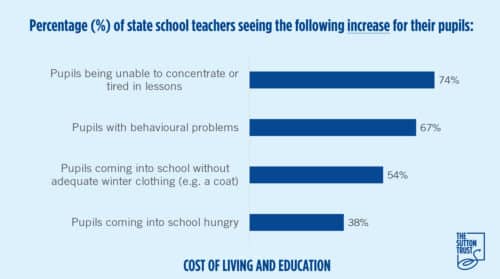

Schools cannot fix all of these issues alone, but they are increasingly expected to fill in gaps in the wider social safety net. Our previous research has highlighted the issues schools are dealing with, such as an increase in the number of pupils coming to school hungry. Many poorer families struggle to cover their food, energy and clothing spending, something that has been exacerbated by the recent cost-of-living crisis.

Figure 3: Percentage of state-school teachers seeing the following increase for their pupils in 2022. Source: Sutton Trust.

The next government needs to take the impacts of poverty out of the classroom, by expanding free school meal eligibility to all children in families receiving universal credit and by supporting schools to increase breakfast club provision – a helping to close the attainment gap.

Ultimately, the source of the attainment gap is the much wider societal issue of socio-economic inequality and poverty. The education system alone cannot eradicate the attainment gap. A true strategy to close the gap for good must include a plan to reduce, and ultimately to end child poverty in the UK.