Press Releases

Our Senior Research and Policy Manager, Rebecca Montacute, and our Research and Policy Officer, Erica Holt-White, take a look at what the return to exams this summer may mean for disadvantaged students.

The last few months have felt like a turning point, as society breathes out a collective sigh of relief at returning to “business as usual”- or something close to it – post-pandemic. It’s understandable that after a difficult few years, many people just want to stop hearing about the pandemic altogether.

Another sign of normality is the return of national exams this summer, back on for the first time since 2019. But students sitting them have been through over two years of disruption, going far beyond the periods when schools were closed. This disruption is likely to have a considerable impact on this year’s results. While society wants to collectively move on from the pandemic, it’s important we still keep the crisis in mind when thinking about exams this year.

What disruption have this year’s GCSE and A level students experienced?

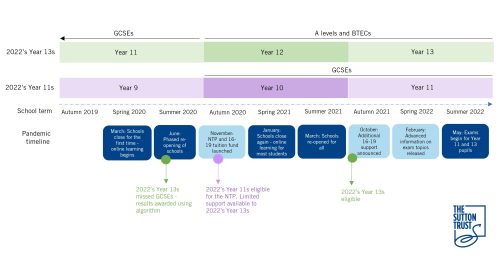

2022’s GCSE pupils haven’t had a full ‘normal’ school year since they were in Year 8, while A level students last had the same when they were in Year 10.

Since then, these students have faced two sets of school closures, and a sizeable amount of disruption even when schools were open, with higher than usual rates of both staff and student absences due to covid infections.

During the periods where schools were closed to most pupils, we highlighted inequalities in access to remote learning, with those from poorer homes much less likely to have the technology, internet access or workspaces needed to learn remotely. While all children faced a large amount of disruption, those from disadvantaged backgrounds suffered the worst impacts.

And disruption didn’t end when students returned to the classroom. For example, earlier this year we found that state schools were much more likely to be affected by ongoing issues with teacher absences than private schools, with state schools in the most deprived areas the most impacted. Throughout the pandemic, at no point has school attendance returned to the average before covid.

Looking at the impact of the pandemic on this year’s exam cohorts specifically – back in early 2020, today’s Year 13s were in Year 11, and due to sit their GCSEs. After their exams were cancelled at the start of the pandemic, Ofsted found that many schools were prioritising learning for younger year groups, rather than those in exam year groups. And researchers found at the start of the first lockdown, while the majority of Year 10 and 12 students were provided with school work, almost half of parents (42%) whose children were in Year 11 – today’s Year 13s – said no remote learning materials were being provided. Whilst these students didn’t have exams to prepare for, the last few months of such a key year in education are important to consolidate learning and nail the basics that inform further study in a particular subject.

Disruption also continued even as young people returned to their classrooms. Education Datalab recently released data on student absences for Year 11s this year, finding students missed an average of 11% of school sessions – almost double the rate for Year 11 pupils pre-pandemic. And again, the impact has been unequal; over a quarter (28%) of students in Year 11 eligible for free school meals have missed the equivalent of at least a day a week over the course of the year, compared with 11% of their peers. These findings are particularly concerning given the established link between higher absence rates and lower levels of attainment.

What do we know about learning loss for this year’s exam students?

We know that the pandemic is likely to have had an impact on the attainment of all pupils, and especially those from the poorest families. A recent review by the Education Endowment Foundation, which brought together existing evidence on learning loss, found there is evidence that the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their better off peers has grown due to the pandemic. And while there has been some recovery since summer 2021, students still have lower performance than equivalent year groups pre-pandemic.

There is unfortunately no work looking specifically at lost learning for this year’s Year 11 and Year 13 students – but from existing evidence it looks likely they will have been considerably impacted by the pandemic. And crucially, these year groups have had very little time back in schools to recover from that lost learning ahead of sitting this summer’s exams.

Another issue for this year’s exam cohorts is familiarity with exams themselves. Usually at this point Year 13s would have sat a full set of GCSEs and associated mock exams previously, but for this year’s cohort, this will be their first formal exams.

What government catch-up support has been available?

The government has announced several measures to support students in the aftermath of the pandemic, including a recovery premium from school aged children of £1 billion running until 2024, and the National Tutoring Programme (NTP) – a sector-led tuition offer delivered through schools. 16 to 19 year olds were left out of eligibility for the NTP, but a 16 to 19 tuition fund was announced, although critics have raised that the eligibility criteria are too narrow, leaving thousands of students without support. In the 2021 spending review last October, an additional £800 million until 2024 was announced for 16 to 19 year olds, to fund an average of 40 additional learning hours for all students to allow for more catch up time.

Many commentators, including the Sutton Trust, have criticised the overall scale of support provided for catch up – with the government’s own “catch-up Tsar” resigning and branding the amount of support on offer as “feeble”. But even aside from these criticisms, as discussed, exam students this year have simply not had long back in school to engage in catch-up support.

What mitigations have been put in place?

Some changes have been made to exams this year in an attempt to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic. Advance information was made available in February on the topics due to be covered in exams for most subjects, to allow teachers and students to focus in during the revision period. For some subjects, students will have a choice of topics or content to answer questions on within exams, so that students can pick questions on topics they have had a chance to cover. And students will also have additional formulae and equation sheets for maths and some sciences.

These mitigations are certainly welcome, but no measures are in place to take into account the uneven impact of learning loss for students from poorer families. Without any such measures in place, there is a real concern that the attainment gap could grow substantially this year. And with harsher grading this year, where grades are being set to a mid-point between 2020 and 2019, there’s a risk some of these students will miss out on the grades they need to go onto their next steps in education, training, or employment.

Another potential issue is what happens to students who contract covid during the exam period and are too unwell to sit an exam. Exams have been spaced by at least 10 days to minimise the impact of a covid infection, so students should be able to sit at least one component of each assessment, and then be given a grade on the basis of what they could sit. Concerns have however been raised that students could potentially game the system – as students can self-certify an infection, they could potentially fake a covid infection to coincide with an exam they feel less prepared for. And whenever a system has potential complexities, for example applying for attenuating circumstances if a student does miss an exam, it is often those from better-off families who was best placed to navigate it.

There may also be issues with the implementation of these mitigations – one exam board has already had to apologise after one of their questions covered topics not included in the advanced information they’d released, with the board announcing all candidates will now receive full marks for that question.

What next?

There are reports of high levels of competition for university places this summer, with warnings universities are reducing the number of places available on popular subjects, after taking on additional students in the last two years due to pandemic grade inflation.

For disadvantaged young people particularly, the pandemic could have a considerable impact on their final grades, and the mitigations put in place this year have not been designed to control for the unequal impact of learning loss on young people from less advantaged backgrounds – putting those students in a poor position in what seems to be a very competitive market.

Contextual admissions and contextual recruitment – taking the context of young people into account when assessing their potential – has been long been championed by the Sutton Trust. This year, that process is more important than ever.

It is vital that anyone making decisions using this year’s results – universities, colleges, training providers and employers – remember that exams this summer will be far from normal – and take that into account when making decisions about candidates.

Today’s young people have just as much potential as previous cohorts – we need to make sure they have the chance to show it, regardless of what happens in their exams this year.