Opinion

School attainment plays a key role in social mobility, with gaps in attainment between socio-economically disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers notably accelerating at secondary school. Over the years, numerous pieces of Sutton Trust research have shown that those from disadvantaged backgrounds fall behind their peers during these years. But what barriers are high attaining disadvantaged students facing in comparison with pupils with the same grades from better-off homes and why is their potential not always fulfilled?

To help answer this, we have launched a new research series, Social Mobility: the next generation. Lost Potential at Age 16 reveals the extent to which the talent of high-potential disadvantaged young people identified at primary-school age is not carried through to age 16 and beyond. We found between 2017 and 2021, over 28,000 young people from less well-off families who demonstrated the potential at primary school to achieve top grades at GCSE did not do so.

Same ability, different outcomes

Our new report is the first research piece to look at the Opportunity Cohort, part of the COVID Social Mobility and Opportunities (COSMO) study, made up of students who were awarded Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs) for their GCSEs in Summer 2021.

Looking at the Attainment 8 measure, which takes grades from a student’s best 8 subjects (with English and Maths double weighted) into account, the average score for disadvantaged high attainers was 64.1. While this is higher than the average score for all students of 53.1, it is notably lower than their more affluent counterparts: other high attainers had a score around 8 grades higher at 72.3 and the most affluent high attainers scored 74.5.

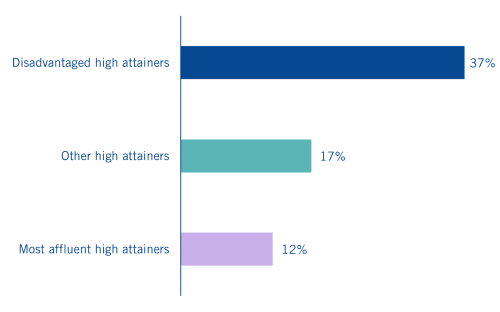

So, on average per subject, disadvantaged high attainers are doing worse at GCSE than their more advantaged peers. This means that proportionally, more of them are falling out of the ‘high attainers’ group; here, we class this as being in the top third of attainers. As shown on Figure 1, disadvantaged high attainers at Key Stage 2 are three times more likely to fall out of the top third of attainers by the time they reach Key Stage 4, compared to their most affluent peers.

Figure 1: Proportion of high attainers at Key Stage 2 who are no longer a high attainer at Key Stage 4, 2020/21

Our analysis reveals some of the reasons why they may fall behind.

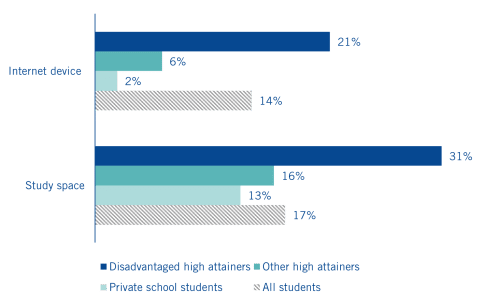

Disadvantaged high attainers are over three times more likely to lack a suitable device to study at home, and twice as likely to lack a suitable place to study (shown on Figure 2 below). They are also less than half as likely to receive private tutoring compared to other high attainers. Furthermore, 16% are young carers – three times more likely than other high attainers (5%). They are also less than half as likely to have a parent with a degree, and four times more likely to live in a single-parent household.

Figure 2: Whether student didn’t have a suitable digital device or study space to work from at home during March 2020 to June 2020 national lockdown (lockdown 1)

Ensuring that socio-economically disadvantaged students with academic potential are able to fulfil that potential throughout their time in education is key for social mobility. However, this new research shows the extent to which this is not happening: this is truly unfair.

The risk to social mobility

Underachievement at this level is likely to hold students back even further through post-16 education and beyond, when they are competing against peers from more affluent backgrounds for university places and graduate jobs. Without adequate intervention, the social mobility of the next generation is under threat.

Addressing the attainment gap at all levels should be a national priority, with a long- term plan in place, based on evidence. To deliver this, funding for schools, particularly in the poorest parts of the country, should be urgently reviewed, so that all state schools can adequately support pupils from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Adequate funding will facilitate the delivery of successful interventions in identifying and supporting highly able disadvantaged students. Our report has 10 top tips for schools and teachers, including:

- To consider designating a team of teachers as highly able coordinators, a group of staff with collective responsibility for implementing programmes and practices for the highly able.

- To use Pupil Premium to ensure disadvantaged highly able students have access to activities and programmes tailored to their particular needs.

- To introduce structured mentoring and tutoring programmes (notably through the National Tutoring Programme using Pupil Premium to subsidise costs).

The fact that disadvantaged students with high potential often underperform in the school system should not hold these students back when they enter higher education. Universities should make better and more ambitious use of contextual offers (including reduced grade offers) and admissions, to acknowledge the attainment gap. This would widen access to higher education, recognising that the playing field is not level at the point of entry to university.

At the Sutton Trust, as part of this new research series, we will continue to follow this cohort of young people as they head to higher education and beyond. To support social mobility for these students and their younger counterparts, national action is vital to ensure that following generations experience a more level playing field than this one has had.

Without this, too many will continue to fall behind.