Opinion

This blog is part of a series looking at challenges and opportunities in education as we come out of the pandemic, based on interviews with a range of experts carried out during 2021.

Vocational training routes, from further education (FE) to apprenticeships, are often overlooked in the UK – especially in comparison to higher education (HE). These options are too often undervalued, with our system commonly criticised as being overly complex, while often failing to meet the needs of both employers and young people.

The vocational system also faced significant challenges during the pandemic. Like HE, FE saw in-person learning suspended and a shift to online teaching, but it also faced considerable additional challenges, for example with work-based training disrupted throughout lockdowns, and considerable economic pressures on many employers making them less able to engage – issues explored in previous Sutton Trust research. Indeed, apprenticeship starts have only recently rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

As we look to build back better after the pandemic, this blog looks at options for reform to improve vocational routes, with our expert interviewees stressing the need for a shift towards higher funding levels, and longer-term, more evidence-based policy making.

Funding and incentives

Generally, our interviewees felt that post-18 funding is skewed towards higher education. For example, one expert highlighted that if someone decides to follow an HE route, they can access about £50,000 worth of government loan support, but there is no equivalent financial support available for those going into FE. There was also consensus that FE funding has suffered significantly in the last decade, with a financial squeeze at all stages, but particularly on adults. Increasing overall funding, including the base rate paid to providers, and recruiting good quality teachers into the sector, were raised as being fundamentals of the system, but it was suggested that because these issues are not headline-grabbing, FE has been starved of funding.

On apprenticeship funding, one interviewee felt that to achieve real traction in the expansion of higher-level apprenticeships, significant investment is required, including a “sea change” in how learning is delivered and embedded, as well as ensuring funding bands more accurately reflect the cost of delivery.

Interviewees also felt that the incentives put in place for apprentices during the crisis were not enough to convince an employer to take on candidates seen as “riskier”, for example those with lower prior qualifications or no or little experience of the workplace, who may need extra support.

On a wider level, some concerns were also raised about the funding given to colleges for mental health support. One interviewee felt funding availability for mental health and wellbeing support across colleges varied too much between different local areas, creating an inconsistent pattern in access, saying that independent providers particularly struggled to access funding. Ofsted recently highlighted learners in FE are struggling with mental health issues, but that learners’ motivation and attendance had increased at some providers with enhanced support measures – showing just how important these measures, and the funding supporting these, can be.

But there was also acknowledgement from our interviewees that increased funding alone was not enough, and that further reforms to the sector are also needed.

Evidence of outcomes

Improvements to evidence on outcomes for young people on different FE pathways was another priority for many. Some felt that there was simply an assumption that undertaking A Levels and progressing to university is the best thing for any individual, rather than knowing whether it is actually effective at helping people meet their career goals.

“Apprenticeships can be great, but we don’t yet have the same kind of outcome data, which helps young people choose one option over another”.

Many felt that without this information, it would be difficult to make changes, and to convince individuals to take different, less traditional pathways.

Interviewees also believed that there was some confusion as to what constitutes ‘good choices’ for young people, and who is best placed to evaluate that. Some interviewees raised that there is more to it than just salaries: for example, one highlighted that a maths degree is not less valuable if someone then becomes a teacher rather than a banker. So there was also a need to look at the skills and jobs the wider economy and society needs.

“We don’t do evidence in the same way for FE as we do for schools, but we need to understand what works for young people to help them get into the labour market. We spend some money on evaluating things, but in post-16 the evaluations aren’t very good, so we don’t understand what works”.

Higher and degree level apprenticeships

Considering higher and degree level apprenticeships, interviewees were very positive about the potential for boosting uptake and were in agreement that apprenticeships were gaining popularity. However, one respondent thought they were still seen as a second choice, with schools solely pushing university routes, and the recent push on apprenticeships at policy level has not translated into schools.

One interviewee commented that while the government wants more people to choose FE and higher-level technical qualifications, they were concerned that it will end up being young people from lower class backgrounds going into FE, whilst middle-class young people continue to go on to HE. They wanted both to be seen on even terms, with students’ backgrounds not determining which route is open to them. Encouragingly, most of our interviewees saw the importance of apprenticeships for social mobility, but some struck a more cautionary tone. One interviewee commented that “Employers need to run their business, not the government’s social mobility strategy”, and that in their view, it does not matter what the government’s aims on widening participation and social mobility are, it is not employers’ primary focus from apprenticeships. Other interviewees commented that the government often treat apprenticeships as if it is the same as FE more generally, rather than seeing the distinctive employer-led nature of these programmes.

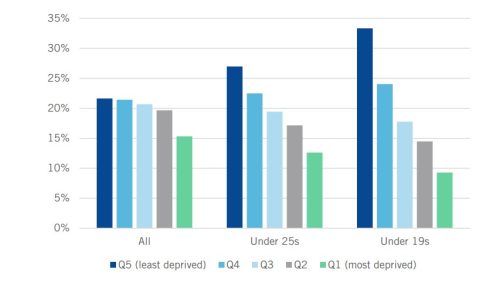

Furthermore, concerns were voiced that the demand for the limited number of higher level apprenticeships was very high, outstripping the supply, making them very competitive. An interviewee spoke about how larger employers are able to offer higher salaries and benefits, resulting in fiercer competition and often more privileged intakes; whereas disadvantaged students end up in lower-paid and lower-level options, perhaps limited to their local area. Indeed, our own research has highlighted that access to apprenticeships for young people and those from disadvantaged backgrounds is an ongoing problem, particularly among the most sought-after apprenticeship opportunities.

Figure 1: Share of higher and degree apprenticeships by deprivation, by age group

Source: Apprenticeship Outreach – Sutton Trust (analysis of DfE data)

One interviewee commented that boosting apprenticeship uptake in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in particular could have a transformational impact. Others commented that improving the overall number of these training opportunities available could support the levelling up agenda; improve diversity in apprenticeships; and help open up opportunities in HE and FE cold spots.

Political focus

Vocational routes have received a welcome amount of political attention of late. The government’s Skills for Jobs White Paper included a number of policies aiming to improve non-academic routes; including the Lifetime Skills Guarantee, providing a new funding route to support flexible lifelong learning; the first Local Skills Improvement Plans, which aim to better match up local employers skill needs with the training offered by colleges and other providers, and efforts to support more people into apprenticeships.

This renewed focus is appreciated, but as highlighted by our interviewees, without enough money behind it, there’s a risk the government misses a real opportunity to transform vocational training, and along with it, the lives of thousands of young people. Greater funding levels, alongside other efforts, like a renewed focus on higher and degree apprenticeships, could help to make the UK an international leader for further and vocational education. The ’employer led’ nature of the apprenticeships programme is currently restricting its potential to deliver both on social mobility and levelling up, and is in need of adjustment. A stronger direction from government, through subsidies, incentives or tweaks to the Levy, to help increase supply and shape where they are located and who they are targeted at, is required in order to realise the transformational potential of apprenticeships

For more information, see our introductory blog, where you will also find links to the whole series.