Press Releases

Our Associate Director of Research and Policy, Carl Cullinane, and our Research and Policy Manager, Dr Rebecca Montacute, explore the inequalities of today’s A-level results.

Results day is always nerve wracking, as young people up and down the country wait to finally see the results of years of hard work.

This year, there’s been an extra worry. Were we about to see a repeat of last year’s omnishambles? And what would that mean for the teenagers whose next steps have been resting on today’s results?

Inconsistencies

Assessments this year have once again been plagued with problems from the onset, with concerns raised by many, including the Sutton Trust, about the fairness of this year’s system.

Crucially, it did not allow teachers to consider individual learning loss, an issue more likely to have affected young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds – who themselves are more likely to have struggled while learning from home, for example due to a lack of equipment or not having a quiet space to study in.

Sutton Trust research has also highlighted issues with consistency, finding large differences in the number and type of assessments used between schools.

Young people have clearly not been on a level playing field this year. Now that results are out, what has this meant for their grades? And how has it impacted university access?

Further rises

This year’s results have once again looked very different from a more normal year, with grade ‘inflation’ rising even higher than in 2020.

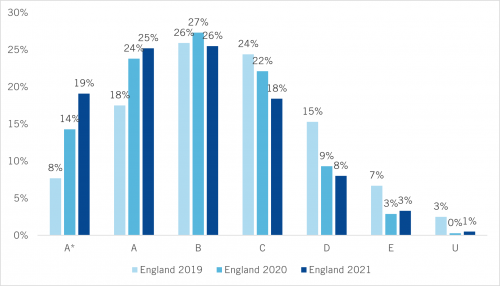

In England, the proportion of students achieving A grades and above have risen to 44%, up from 38% last year and 25% in 2019. Most of this growth is in those gaining A*, which has increased to 19%, up from 14% previously. In contrast, inflation has been much lower at the C grade boundary, at less than 1 percentage point.

A-level grades over time in England (2019-2021)

Much of the criticism today has been on this inflation, with concerns that students’ grades are being ‘de-valued’. It was however somewhat inevitable in a system which allowed so much variation, without a clear basis on which teachers could award grades consistently.

On top of that, some students would have just had a bad day when they come to sit an exam. But a system based on teacher assessment could never have hoped, nor should have it attempted, to predict which students that would have been. Determining grades from assessment which could take into account a range of work from different time points was always likely to lead to higher grades overall.

Worsening inequalities

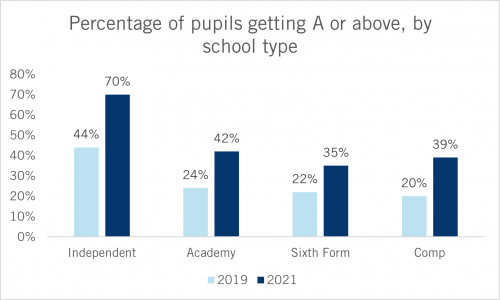

Today’s results day has also shown growing gaps between independent and state schools when it comes to the top grades.

Private schools have seen the largest absolute increase in grades, with 70.1% achieving A or above, up 9.3 percentage points on 2020. Conversely, there has been a smaller increase in most other centre types, with 39.3% achieving A*/A in comprehensives, a 6.2 percentage point increase from 2020; 41.9% at academies, a 5.7 percentage point increase; and 35.3% in Sixth Forms, up 3.8 percentage points on 2020.

The difference in relative growth between the independent and state sector is however less stark, with independent schools starting from a high base rate of A grades.

Looking at free school meal eligibility, a marker of socio-economic disadvantage, there is also evidence of gaps widening throughout the pandemic. The attainment gap for A grades and above has risen from 7.7 percentage points in 2019, to 10.55 percentage points in 2020, and now stands at 11.9 percentage points.

Gaps in who gains the top grades have obvious knock-on implications for admissions to selective universities. Looking at grade combinations also emphasises the challenges for university admissions tutors this year. In 2019, 18% of students achieved AAA or higher from three A-levels. This year that has more than doubled, to 37%.

Access gaps widen

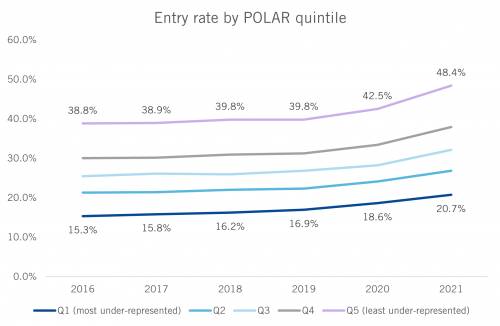

What has all this meant for university access? So far, the picture is mixed, showing progress in university access among under-represented groups, but this growth outstripped by advantaged groups. While the overall entry rate for 18-year-olds in the UK is at a record high, now at 34.1% (compared to 30.2% in 2020 and 28.2% in 2019 at the same stage), and participation rates for students from under-represented areas is also at a record high (20.7%, compared to 18.6% last year), gaps between groups have widened.

This is due to surge in entrants from areas already well represented in higher education, with the entry rate for areas which already had higher rates of participation up at 48.4%, an increase of 6 percentage points from 2020. And while the entrance rate has increased for those from less well represented areas, the rise has been much smaller, from 18.6% in 2020, to just 20.7% in 2021. This means that the entry gap has grown, from about 24 percentage points in 2020, to almost 28 percentage points today.

Decisions, decisions

While many decisions on final places will have already been made by universities, the Sutton Trust strongly advises those who are still making any decisions on places (including those perhaps waiting on appeals or looking at taking students through clearing) give additional consideration to students from lower income backgrounds.

Doing so can help to take into account the challenges this group have faced during the pandemic, challenges which were not reflected in this year’s assessment system, and would help to ensure students don’t miss out who have been impacted unfairly by the system this year.

Onto the autumn

It’s also vital to remember that behind all these numbers are real young people, who have worked hard through extremely challenging circumstances. Through no fault of their own (and despite their higher than usual grades), many have missed out on significant learning during the pandemic, and are likely to need additional support when they arrive on campuses or onto apprenticeships or other training this autumn.

It may be too late to fix this year’s assessments, but more can now be done to make sure this group of young people get the help and support they deserve going forward.