News

Our Early Years Lead, Laura Barbour, and our Research and Policy Manager, Dr Rebecca Montacute, discuss our latest research which explores inequalities in access to early education.

We wouldn’t accept the state providing longer hours in school for better-off families – but this is exactly what is happening in the early years.

In England, while all three-and-four-year-olds are entitled to 15 hours of early education and childcare per week, since 2017, children in ‘working families’, those who meet certain criteria, are able to access an additional 15 hours on top.

Many low earners in work do not earn enough or work enough regular hours to qualify.

This means the current policy disproportionately benefits more advantaged families, with research in the Sutton Trust’s new report, released yesterday, A Fair Start? finding that 70% of those eligible for the full 30 hours are in the top half of earners, while just 13% of eligible families are in the bottom third of the income distribution. It’s clear a change in policy is needed.

How did we get here?

There were good intentions behind the introduction of the 30 hours policy, which looked to increase availability and affordability of childcare for working parents. But the design of the policy has not met those objectives. And the focus on childcare alone has ignored the important role played by early years education, especially for the poorest children.

Prior to the pandemic, the government had celebrated an overall increase in the percentage of children reaching a good level of development at the beginning of school. This is to be welcomed, but at the same time efforts to close the school readiness gap had stalled, and the gap had started to widen again. Today’s research has found evidence that the existing 30-hour policy may be contributing to this growing gap between the poorest children and their better off peers.

There is also a risk that this will be made worse by the pandemic, with our research finding that 54% of primary school senior leaders think fewer children were school ready this year than they would normally expect before the pandemic. The very youngest children have often been left out of conversations on the impacts of the pandemic, but they too have missed out on important experiences with wider family, friends and their wider communities. If we don’t act now, we risk poorer children being behind for the rest of their education.

What should change?

In today’s report, a range of experts have looked at the 30 hour policy and options for reform in detail. These options include extending the entitlement to disadvantaged children based on the criteria used for the disadvantaged two-year-old offer, and making the entitlement universal.

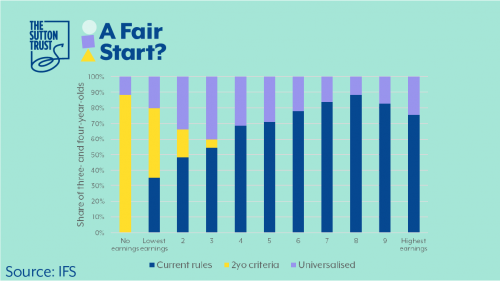

How each policy would impact families at different earnings levels is shown in Figure 1 below. While extending to disadvantaged children based on the two year old offer would bring many children from poorer homes into eligibility for the first time, it would still leave many of these families without access, who would be brought in under a universal entitlement.

Figure 1: Share of three- and four-year-olds brought into eligibility under different criteria, by household earnings

Universal or a targeted expansion?

We’re recommending the 30 hour policy is made universal for all three-and-four-year olds. As well as bringing all the families who need it into eligibility, a universal offer would have several other benefits, including a reduction in administration for families, providers and local authorities, all of whom currently have to prove or check eligibility on a termly basis, and improved financial security for settings. There is also less risk of excluding those families on the threshold of eligibility.

We spoke to one family whose case perfectly illustrates issues in the current system. As a paramedic, she works part time and irregular shifts, and is unable therefore to access the entitlement for her three-year-old. This limits the flexibility she can give to work, and reduces access to early years education for her child. The existing policy isn’t working for parents like her, and it needs to change.

Funding levels

75% of the early years providers surveyed here reported that the current funding levels provided for the 30 hour entitlement do not meet their costs. Inadequate funding rates have a potential impact on quality, and result in providers having to make additional charges to ensure survival, which can exclude eligible working families on low incomes, who can’t meet these additional costs.

Given that, some have argued it would be better to focus on improving quality by increasing funding for the existing entitlement, rather than expanding it to more children. But we strongly believe that this simply cannot be an either-or question. If quality is improved first, but access is not widened, then the 30 hour entitlement risks widening the attainment gap even further, as the poorest children will not be the ones to see the benefits. But equally, it would be wrong to expand the entitlement without efforts to improve quality. Simply providing disadvantaged children with more hours of provision which are of a low quality would not provide the necessary level of support these children need to improve their academic and social outcomes.

Alongside a move to universal access, we also need to see an increase in funding. At a minimum, the government should provide additional funding for disadvantaged children, for example through increasing the Early Years Pupil Premium. This will ensure that hours provided are of a high quality and serve the poorest communities.

Providing additional funded for disadvantaged children also has the added benefit of providing settings with an incentive to recruit children from families on low incomes, as well as ensuring settings serving the poorest areas remain sustainable into the long term.

And importantly, the sector would largely be able to expand the current offer, and most would offer it, as long as their costs are met. On this basis, almost 80% of early years settings surveyed would favour extending the current offer to disadvantaged children and 40% would support making it fully universal.

What about quality?

If additional funding is provided, we also think it should be tied to quality. That’s why we’re recommending that in order to qualify for extra funds, providers should be required to meet certain evidence-based quality criteria, for example employing a graduate leader in their setting, employing a certain proportion of Level 3 qualified staff, and providing professional development opportunities to their workforce. The Trust also wants to see the re-introduction of the targeted ‘Leadership Quality Fund’, to improve pay and conditions for staff, so that settings, particularly serving less advantaged communities, can attract and retain a well-qualified workforce, as well as invest in CPD and career pathways.

How realistic is a change?

There are a range of financial models suggested in the report. Given the return on investment they are not radical. For example, an extension to a universal entitlement for all three- and four-year-olds was estimated to cost £250 million in the IFS’ central scenario, an increase in overall spending on the existing entitlements for this age group of just 9%, and a change which would extend eligibility to 80% of children in the bottom third of the income distribution for the first time.

Universal high quality early education and childcare provision is vital to close the inequality gap that too many children experience, and which the pandemic risks further widening. There must be equal access for all children to learning, playing and socialising with their peers. Flexibility and choice are also essential for all parents pursuing work, study or training opportunities. Transforming this policy should form the backbone of the post pandemic recovery and ensure a fair start for all children in the future.

Find about more about our campaign to make access to early education fair for all.