Press Releases

Our Research and Policy Officer, Erica Holt-White, explores the findings from our latest report on careers guidance in secondary schools.

Good advice and information on careers can empower students to make informed decisions about their future pathways. With an ever changing world of options, including the launch of T-Levels and the continuing growth of apprenticeships, this guidance is more important than ever. All young people should be receiving high-quality and impartial careers guidance.

It is also a core element of social mobility. Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to have access to a wide range of knowledge and guidance from family and friends, or to have networks which provide an insight into a range of career options. Good quality careers guidance can help to level the playing field.

When we last published research on careers guidance in our report Advancing Ambitions in 2014, we found a ‘postcode lottery’ of provision, with significant variability between schools.

Since then, the policy landscape has changed considerably, with positive changes such as the establishment of the Careers and Enterprise Company to support schools with their provision.

But while there have been improvements, our new report, released today, has found there is still far too much variability – with the biggest differences between state and private schools.

Indeed, it is clear that careers guidance is not working for all students, with our research finding that 1 in 3 secondary school pupils are not confident about their next steps in education and training.

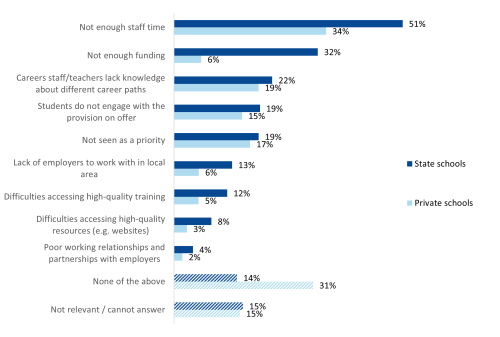

Barriers teachers face to delivering high quality guidance

Our polling of teachers found the most common barriers schools face to providing high quality guidance were staff time and funding with those working in state schools more likely to report these barriers than those in state schools (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Barriers to delivering careers education and guidance, by school type

There are also differences between the most and least deprived state schools – 21% of teachers in the most deprived areas reported non-specialists delivered personal guidance at their school, compared to only 14% in more affluent areas.

Teacher training is another barrier, with over three quarters of state school teachers (88%) saying that their teacher training didn’t prepare them to deliver careers information and guidance to students.

A new national strategy on careers

We found that while there are aspects of good practice when it comes to careers guidance, there is no overarching strategy to link elements up across the system. Indeed, there is currently no national government strategy on careers guidance, with the 2017 strategy allowed to lapse without replacement.

That’s why we’re calling on government to write a new national strategy for careers guidance, setting clear aims to improve provision. This strategy should be cross-departmental and tie to the government’s Levelling Up agenda, with a focus on improvements in the country’s poorest areas.

At the core of any new national strategy should be a ‘Careers Structure’ for all secondary schools, with the funding to go along with it. This should involve three key elements -all schools should have a Careers Leader with the time, recognition, and resources to properly fulfil their role; be part of a Careers Hub; and have access to a professional career adviser for their students (qualified to at least Level 6).

Greater time should also be earmarked and integrated within the curriculum, so teachers and Careers Leaders have sufficient time in the school day to deliver careers guidance. Clearer requirements should be set for time spent on overall careers guidance (for example in PSHE lessons or as a scheduled careers week for pupils) as well as for subject specific careers guidance within lessons. This should be accompanied by better training for teachers on careers education within initial teacher training.

Better guidance on apprenticeships

Today’s report also includes polling of students, to examine not just what is being offered by schools, but the activities that young people are actually taking part in.

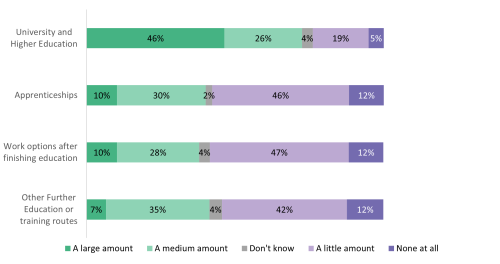

One of the big disparities in students’ own experiences was the difference in reported guidance on technical education routes, with students in year 13 4 times less likely to have received a ‘large amount’ of information on apprenticeships than on university (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of year 13 students who had received guidance about particular routes during their education

More investment is urgently needed in both programmes and information sources on technical education routes to improve the advice available.

Evidence suggests that many schools aren’t meeting their statutory requirements under the Baker Clause, which requires schools to allow college and training providers access to students in years 8 to 13 to inform them about technical education and apprenticeships. Better enforcement should be introduced, for example looking at incentives such as limiting Ofsted grades in schools who do not comply with the clause.

Work experience opportunities

Evidence shows that work experience is an invaluable opportunity for young people, allowing them to see a workplace and develop life-long skills that should be accessible to all. However, here we find that less than a third of year 13s have completed work experience.

We’re recommending all pupils should have access to work experience between the ages of 14 to 16. This is a time period when students are about to make key decisions about their future, whilst also mature enough to enter a workplace.

Students should be supported by their school in finding a relevant and valuable placement. Given the potential challenges for schools, they should be offered support and resources needed to do this well. Employers should also be supported with logistical and issuance issues when delivering these placements.

Moving forward

Offering high-quality careers guidance to all individuals in every school and college is vital for social mobility; opportunities from speaking to a Careers Adviser, to completing work experience can provide invaluable insights into particular pathways, which those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds may not otherwise see.

The priorities outlined here have the potential to transform provision, so that all students can make informed decisions about their future.