Press Releases

Ahead of results day, Rebecca Montacute and Georgia Carter provide an overview of the challenges this cohort of students have faced and what information to look out for on the day.

Results day is again just around the corner, the second year with a return to exams post-pandemic.

As another cohort waits nervously for results, this is a group of young people who have been heavily impacted by both the pandemic, and the ongoing cost of living crisis to boot.

What’s important to know about this group of students ahead of year’s results day? And what could it mean for social mobility?

The Class of 2023

The students who will crowd into schools to pick up results envelops for A levels and other qualifications this Thursday have had a long road to get there.

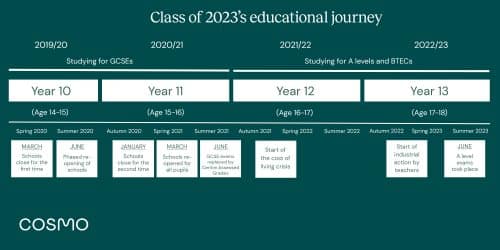

They were in Year 10 at the start of the pandemic, missing large parts of their GCSEs during lockdowns, before their exams in Year 11 were eventually cancelled and replaced by Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs). For those who sat exams this summer, they will have been their first experience of real exams, under exam conditions.

The COVID Social Mobility and Opportunities Study (COSMO) has been following the experiences of this year group, from the pandemic and beyond. Our research found large differences in remote learning for this group during the pandemic, especially between state and private schools. And barriers to remote learning – such as lack of access to a suitable device for learning or sharing a device, lack of a quiet space in the home, lack of support from teachers or parents – were all more likely to be experienced by young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

When they were in Year 12, many young people in this group felt they had fallen behind due to the pandemic, with almost half (46%) of students at comprehensive schools saying they had not been able to catch up with learning, a significantly higher proportion than those at independent schools (27%).

In recent in-depth interviews with young people in this group, we found concerns around gaps in their knowledge from GCSE, as well as difficulty concentrating after periods of online learning. Other discussed the challenges of preparing for A levels, having missed out on doing so at GCSE level –

“The GCSEs they weren’t proper exams, they were like 15 minute tests (…) We didn’t have to do a lot of work and that’s impacted me now because right now it’s hard for me to revise like I don’t know the techniques.”

“Because of COVID there was a lot of content that we missed out on (…) A lot of the content also got cut out of the GCSEs.”

And new analysis of questions asked to this group of young people during Year 13 (based on data from COSMO wave 2), has found a third (33%) still feel the pandemic is having a negative effect on their education or training.

What’s the plan for exams this year?

In England, Ofqual are aiming to return to pre-pandemic grading standards this year, although they have built in some protection to recognise cohort-wide impacts from COVID. Ofqual have explained the protections in place, with an example student who would have achieved a B in geography before the pandemic being just as likely to get a B this year, even if their performance in exams is a bit weaker.

However, while this approach does recognise cohort-wide effects of the pandemic, it isn’t able to take into account individual level learning loss, which we know is much more likely to have impacted lower income students.

Can we get any clues from what happened last year?

A level results

2022 was the first year which saw a return to exams, where the impact of the pandemic could be seen clearly in results.

Concerningly, that year saw the A-level disadvantage gap at its widest since records began, with the gap in average point scores between disadvantaged and wealthier pupils at 5.09. This compared to 4.51 when teacher grades were awarded in 2020-21 and 4.88 in 2018-19, when exams were last sat. The increase in this gap was largely driven by disadvantaged students with higher prior attainment at GCSE level falling behind.

The gap in A level results between independent and state schools had also widened since before the pandemic, although it was lower than the gap seen in 2021.

Last year was also the first year in which Ofqual started the process, continuing this year, of bringing A level grade inflation back down to pre-pandemic levels. The proportion of A Level grades at A and A* went down from 44.8% in 2021 to 36.4% in 2022 across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, compared to 25.4% pre-pandemic in 2019.

University access

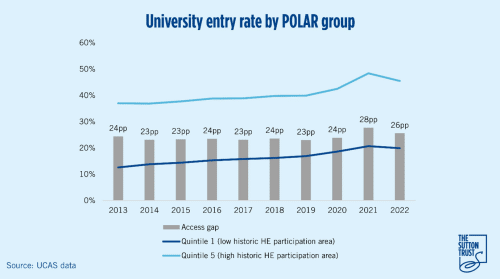

245,100 18-year-olds were accepted to university in 2022 across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, an increase on both the last few years and on numbers pre-pandemic. The entry rate last year was 32.2%, lower than in 2021 (34.1%), but higher than 2020 (30.1%) and pre-pandemic in 2019 (28.1%).

While the gap in access between young people from areas with high historic participation in higher education (Q1) and those with low historic participation (Q5) did narrow last year compared to 2021, it was still larger than it had been pre-pandemic.

What to look out for on the day

On Thursday, we’ll have information on overall A level grades, as well as comparisons between state and private schools. One of the key questions will be whether the attainment gap between these two groups has continued to narrow, and how it now compares to the gap pre-pandemic.

We’ll also have information on overall university entry rates, as well as what has happened to the access gap, as measured by historic participation rates of areas in HE. With grade inflation coming down further, and likely more students than ever missing their predicted grades, one of the key questions will be how this will impact university admissions, and whether universities prioritise the young people who faced the greatest challenges during the pandemic.

We know that grade inflation did not fall as much as Ofqual had planned for in 2021, so another important question for the day will be whether the ‘glide path’ back to pre-pandemic standards will fall short again in 2023, or if there will be a larger drop.

According to the Centre for Education and Employment Research (CEER) at the University of Buckingham, the percentage of A*s will have to fall from 14.6% last year to 7.8%, meaning we could see 59,000 fewer A*s and 36,000 fewer As in 2023.

And what we won’t know this week

One question we will have to wait longer to answer, with information on the attainment gap between disadvantaged students and their more advantaged peers not available until later in the year, is who exactly will shoulder the burden of this grade deflation post-pandemic.

There is a real concern, given differences in experiences during the pandemic and the widening of the attainment gap seen with the return of exams in 2022, that lower income students could feel the biggest impacts of this return to pre-pandemic grading.