Press Releases

This blog is part of a series looking at challenges and opportunities in education as we come out of the pandemic, based on interviews with a range of experts carried out in 2021.

As we highlighted across our research during the Covid-19 pandemic, when education settings were closed, those without the right devices or internet access at home were at significant disadvantage during periods of remote learning. Parents with young children were unable to connect to their usual early years providers; school, college and university students could not engage with online lessons; and those looking to gain work experience were blocked from accessing virtual versions of those opportunities. Even though education settings have been open since spring 2021, these issues have not gone away, with the closure of class bubbles, staff absences and individual Covid cases once again sending pupils back home to learn.

Whilst the vast majority of students had never taken part in online lessons before Covid-19, the digital divide itself certainly isn’t a new issue. Data collected before the pandemic found that likelihood of internet access increased with income, with households with an average income of £6,000 to £10,000 half as likely to have access compared to households earning over £40,001.

To reduce the divide, stocks of school-provided IT equipment substantially increased over the pandemic thanks to investment from schools themselves, government funding, as well as charitable donations. However, research conducted in the current year indicates there are still gaps in access. Digital learning has been massively accelerated by the pandemic, and now that it has been established, seems set to continue in the long term. The government’s ‘online school’ Oak National Academy, set up during the pandemic, has recently been put on a permanent footing. This growth in online learning creates opportunities to widen access to resources and support, as well as more flexibility to tailor learning to student needs. But ongoing gaps in access to IT risks entrenching disadvantage for students from poorer backgrounds.

A universal problem

Our interviews with experts across the education sector made it clear that there is a digital divide for children and young people of all ages.

Those working in the early years pointed out that it was difficult for settings to communicate with parents during the pandemic if they didn’t have internet or an appropriate device. Those living in rural areas also had issues with internet connectivity. An interviewee pointed out how these issues will persist even now that early years settings are back open, as more advantaged parents will continue to use digital technology and online resources for learning and development activities at home; something not possible for those without IT access.

Experts in the school sector also felt that digital learning was likely to continue and grow, highlighting the use of resources such as Oak National Academy and revision websites. Some interviewees thought permanent home schooling may increase (evidence suggests this is already happening) and stressed the importance of continuing to tackle the digital divide. They flagged how families had to share internet-enabled devices, which meant pupils could not always engage with lessons, and how schools had to fund as well as crowdsource laptops for their students.

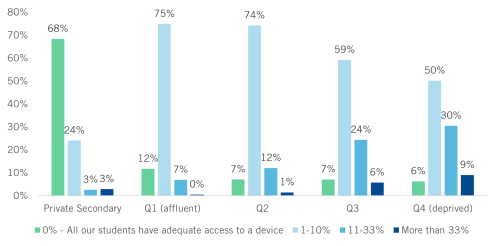

Whilst the government distributed over 1.3million laptops as part of their Get Help with Technology programme during the pandemic, this did not happen straight away. In December 2021, only 13% of teachers overall reported that all their students had adequate access to a device for remote learning, with access less likely for those in more deprived schools (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of a teacher’s class who lack a device for learning in December 2021, by deprivation level of school

Despite the push for equipment in schools, not all young people in education or training were covered. Interviewees in the FE sector flagged that this kind of support was not on offer to their students, even though access to the internet was just as important. Others mentioned how little research was done on the digital divide for FE students. The Trust supplied laptops to hundreds of post-16 students during the pandemic, thanks to funding from XTX Markets – and we are still supplying laptops to those who need them.

Moving forward, interviewees raised concerns about how the digital divide will affect pre-apprenticeship recruitment and training, which is mostly done online.

“We haven’t seen apprentices helped in the same way by providing laptops – digital access hasn’t been reported on, so we can’t say X number of apprentices couldn’t take part remotely because of a lack of device. We know from providers that this has certainly been an issue”.

Again, those working in higher education also noted digital access barriers for disadvantaged students. As well as access to the internet, barriers also included suitable study space, particularly in halls of residence or Houses of Multiple Occupancy (HMOs), where space may be cramped and facilities like communal workspaces may have poor quality resources (such as computers). If blended learning is to become a permanent fixture at universities, such issues will persist.

A space for innovation

The continuing issue of the digital divide makes for grim reading. However, our interviewees did share some positive views on the use of digital technology in education. One from the schools sector thought digital innovation had improved collaboration and flexibility for the teaching profession. Others felt that there might be benefits to developing digital forms of assessments to simplify the assessment system, and to make it more resilient to shocks like those the pandemic created. The opportunity for online resources to allow students to pick up subjects of interest outside of the classroom was also highlighted.

Further Education experts also thought that lessons could be learned from the pandemic to create innovations in FE programmes, such as digital lessons. One interviewee highlighted that moving to online exams had been a real positive for some young people who do not enjoy or thrive on typical, stressful exam conditions, particularly those doing lower-level apprenticeships.

Others commented that whilst over time there have been improvements in online pedagogy, there is still a need to continue to invest in this so technology becomes a genuine asset, and that providers are not just delivering the same content through a screen, which some were concerned had happened during the pandemic.

Those working in Higher Education thought that blended learning is likely to continue, as it has suited learners who prefer more time off-campus, but they wanted to see better training available for staff to deliver engaging online lectures. They also thought it would allow increased engagement between university staff and students, observed during the pandemic, to continue.

“We should take the things from moving online that have worked well forward – better engagement, better attendance, better feedback, and more meetings between staff and students”.

Even still, interviewees raised concerns that this approach would not suit those with digital access issues. Improving university IT rooms, creating social learning spaces on as well as off campus, and revitalising the design of student accommodation were put forward as solutions.

Closing the divide

The pandemic exposed the issue of the digital divide, and underlined the need to address it, not just while education settings were closed, but in the long term too. Organisations like the Carnegie Trust have campaigned on the issue for a long time, stressing the educational disadvantage of not having internet access to complete schoolwork and revision at home. They have also highlighted the wider impacts of digital exclusion, from the inability to develop digital skills for the world of work to being unable to socialise online with their peer group.

Even now that education settings are physically open, students will continue to need access to the internet from home for a range of reasons, including to complete homework and to take part in online lectures. And as highlighted in our previous blog, which discussed the cost of living crisis, as heating bills increase and more families are likely to enter poverty, more children could lose access to the internet outside of school. As is stands, this issue could get worse before it gets better.

At the Trust, we want to see a guarantee that disadvantaged young people have internet access, facilitated by laptops and internet dongles that can be lent out by schools and colleges. Educational websites should also be excluded from data allowances on an ongoing basis. The pandemic rapidly accelerated the adoption of digital learning as a core part of education provision. It is now absolutely fundamental to the fairness of our system that the digital divide is closed and remains closed in the future.

For more information, see our introductory blog, where you will also find links to the whole series.