Opinion

This blog is part of a series looking at challenges and opportunities in education as we come out of the pandemic, based on interviews with a range of experts carried out during 2021.

The final Covid-19 related restrictions in England were removed by the government several weeks ago – but for many young people and families, this turning point did not mark a return to life before the pandemic, with many still living with the long-term impacts.

While a major focus over the past two years has been on remote learning, cancelled exams and widening attainment gaps, the pandemic’s impact on young people hasn’t been limited to their schooling. It has also impacted the financial security of many families and had a profound effect on the wellbeing and mental health of a generation of children and young people.

The emotional and financial impacts of Covid were consistently raised by our expert interviewees when we asked about the interventions required to support children as we emerge from the pandemic.

This is unsurprising, given it has been estimated that over 10,000 children in the UK lost a primary caregiver due to coronavirus in the first 20 months of the pandemic; referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) were up by 134% compared to spring (April to June) 2020, and 96% up on 2019; and there have been considerable financial pressures for many families – with over 6 million employees furloughed or made redundant between .

This made it difficult for thousands of families to make ends meet and support the needs of their children. And whilst unemployment has now recovered, many households are facing a major hit to living standards, driven by rising inflation and threatening a new child poverty crisis. Our interviewees were clear that such hardship can both directly and indirectly impact the mental wellbeing of the whole family – including young children – and more children living in poverty means more children that are not in a good place to learn, as they may be arriving hungry or cold. For schools with high proportions of pupils in poverty and/or experiencing mental health problems, this increases the need for and strains on pastoral services from already stretched schools.

Mental health and wellbeing

During our interviews with those working in the early years sector, several experts mentioned the mental health impact the pandemic has had on both parents and young children, often compounding difficulties already experienced in the home. They wanted to see early years providers work to identify and support families experiencing such difficulties, so that children could thrive and engage in early years settings.

One interviewee highlighted how bereavement may have affected many children during the pandemic, and the importance of ensuring that practitioners are trained to deal with such sensitive matters. Another interviewee wanted to see more health visitors working in early years settings to support staff.

“Disadvantaged children often have to cope with bereavement and loss. This is likely to have increased during the pandemic. Practitioners have identified it as an issue and requested more support and training so that they are able to support the children appropriately”.

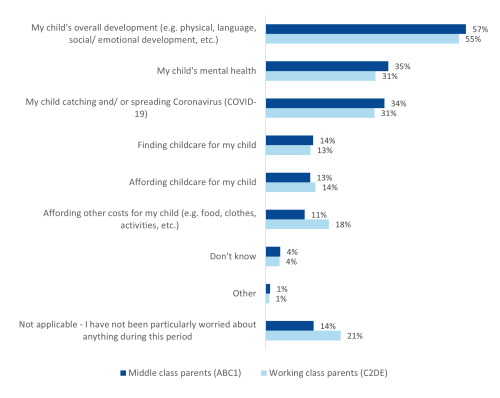

These issues were even more apparent to the Trust following a survey of pre-school parents in 2021 as part of our Fair Start Campaign – 64% of these parents had been worried about their child’s development or wellbeing during the pandemic. Over half (52%) said their child’s social and emotional development had been harmed. These concerns were apparent for both middle class and working-class parents (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Worries of pre-school parents during the pandemic, by parental occupation

Comments were also made on welfare and health services in schools. Experts wanted increased investment in school welfare services, such as psychologists, and emotional support made a key part of post-pandemic recovery plans. One interviewee was keen to see research investigating how the usage of mental health and social services varies between levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. The first wave of our COSMO longitudinal study will help to further build understanding of the mental health and wellbeing impacts of the pandemic on teenagers.

Supporting children

The pandemic has affected children’s mental health in many ways, ranging from bereavement and grief after losing a loved one to increased levels of anxiety after being indoors away from large groups of people for a sustained amount of time.

As heard from our interviewees, education staff have truly stepped up to support children who have suffered mentally during the pandemic. But intervention at the top level is still required.

In 2021, Young Minds called for wellbeing to be a significant part of catch-up plans in schools and for increased ringfenced funding for mental health services in schools. Action for Children also want to see increased funding for health visitors, so they can identify mental health issues in young children that have emerged during the pandemic. Others have called for significant additional funding for overwhelmed Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

At the Sutton Trust, we will continue to work with Young Minds to ensure all students taking part in our programmes have access to high-quality mental health support. We also welcome the recent pledge in the government’s schools White Paper that every school should have access to funded training for a senior mental health lead – this should be delivered as a matter of urgency. However, the pandemic should serve as a clarifying moment for finally taking serious action to address the crisis in young people’s mental health that has been building long before 2020, with a joined-up approach needed across the NHS, local authorities and schools.

Entering poverty

As well as the stark impacts of the pandemic on mental health, many experts we spoke to highlighted the financial impacts that have sent many families into poverty, and how this intertwines with education.

Interviewees mentioned digital access issues, as well as the financial constraints of having internet enabled devices and a good quality internet connection at home. One interviewee also raised the wider issues related to digital access faced by families – for example, the higher electricity costs accompanying laptop usage for schoolwork in homes. This digital divide is something we will discuss in more depth later in our blog series.

Interviewees also highlighted how schools had to urgently support those from the poorest families at the start of the pandemic by delivering food packages and supplying digital devices. Some spoke of the wider impacts of poverty on education, particularly the negative impact on engagement in the classroom.

“Poverty is not just educationally damaging but it has other impacts. When poverty is relieved, students can learn better and their parents can support them better”.

In terms of improving support for the poorest families as part of pandemic recovery, a group of participants in the early years sector mentioned the potential importance of Family Hubs and Sure Start centres, calling for significant further investment. Local leadership, targeted recruitment and community involvement were highlighted as the elements that are key for success in reaching disadvantaged families.

Schools experts also wanted to see better collaboration between the services working to support families experiencing poverty within the community.

To support families at or below the poverty line at the outset of the pandemic, the government introduced a £20-a-week universal credit uplift. Often described as a ‘lifeline’, this has now been removed, but the issues it was implemented to relieve are far from over, and with an escalating cost of living crisis, the recent Spring Statement has come in for significant criticism for not moving fast enough or far enough to protect families.

Policy priorities

This rising cost of living raises the urgency of action, as over a million people are predicted to enter poverty from April, and absolute child poverty is projected to rise by 5 percentage points between 2020-21 and 2022-23. Organisations including the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have called for a variety of actions, including raising benefits as close to inflation as possible in April, to support those worst hit by the cost of living crisis.

The Trust’s work focuses on the role of education in providing opportunities for young people to escape disadvantage. However, the education system on its own cannot be expected to solve deep-seated inequalities in life circumstances. With inequalities in circumstances outside the school gates worsening further in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, issues of educational inequality and social mobility will not be fixed solely by schools and universities.

Whilst the interventions required to support those affected by the pandemic go far beyond the contents of one blog post, it is vital to recognise the disproportionate and wide-ranging impacts of the pandemic on the lives of young people from poorer homes, both within and beyond the school gates.

For more information, see our introductory blog, where you will also find links to the whole series.