Opinion

The government has failed to commit to funding for the National Tutoring Programme (NTP) for the next school year. Despite the initial challenges in rolling out the scheme during the pandemic, this is extremely short-sighted given the widening attainment gap between pupils from poorer backgrounds and their wealthier peers, and the established evidence on the effectiveness of tutoring.

The argument is that tutoring is something that schools should be funding through existing pupil premium funding. However, this move also comes at a time when schools are increasingly using their pupil premium money to plug holes in their general school budgets, and the value of that funding is failing to keep pace with inflation. Now is absolutely not the time to be abandoning one of the few educational interventions in recent years with the prospect of truly addressing longstanding educational inequality.

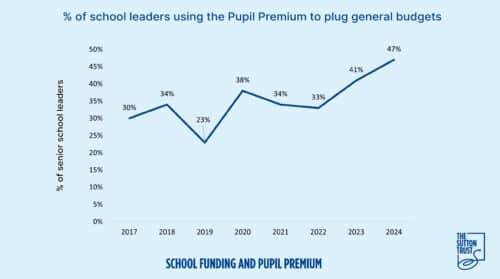

Pupil premium funding is specifically intended to support schools with provision for disadvantaged pupils, such as tutoring. But recent polling from the Sutton Trust has found that the proportion of school leaders using it to plug gaps in their budgets has risen to 47%, the highest level since we first tasked the question in 2017.

Pupil premium funding being used to plug gaps in general budgets since 2017

Furthermore, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), pupil premium funding is about 14% lower in real teams in 2023-24 than in 2014-15. What all this means is that schools find themselves with less money to spend on supporting students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, underscoring the importance of ringfenced funding for the NTP.

The NTP was set up in 2020-21 and funded by the Department for Education (DfE) to provide subsidised tuition to support disadvantaged pupils and address the problem of educational disparities arising during the pandemic. In the latest iterations of the NTP, schools are offered three kinds of support: academic mentors, school-led tutoring or tutoring through tuition partners. Funding has been allocated according to the number of pupil premium eligible pupils in the school. And although schools have flexibility as to how they deploy the resources, they have been encouraged, though not restricted, to focus interventions on more disadvantaged pupils.

Despite some inevitable teething problems in the first years, the programme has been widely welcomed by school leaders, teaching unions and others as a much-needed resource given that since the pandemic, the attainment gap has widened again to levels not seen for over a decade. Recent evaluation of the programme conducted by NFER on behalf of DfE found the perception in schools that: “involvement in the NTP was helping to improve outcomes across schools more broadly (for example, by helping to close the attainment gap for the school overall). The NTP was perceived to be an important and effective programme in supporting pupils most disrupted by the pandemic” (p.11).

Our research in 2023 also found that the NTP had a significant impact on the distribution of tutoring among sectors of the population, with 41% of year 11 pupils being offered some kind of school tutoring in 2020/21, compared to only 9% having private tutoring at that time. The research also found that while the most deprived areas have the lowest rates of private tutoring, through the NTP they have come to have the highest rates of school tutoring.

The NTP is not perfect – it needs to more effectively target the most disadvantaged pupils for instance. However, it is one of the most directly effective educational interventions in recent years aimed at closing the attainment gap. This is why the Sutton Trust has called for whoever forms the next government to commit to long-term funding of the NTP or a similar scheme targeted at disadvantaged pupils as part of a national strategy to close the attainment gap.

This is also why the NTP remains popular among school leaders. Our polling has found that, despite government cuts to NTP funding this year, almost half of school leaders said they still used it over the last year for either tuition partners, academic mentors or for school-led tutoring sourced locally. In fact, there was a slight increase among secondary senior leaders using the NTP, up to 58% compared to 56% in 2023.

Government funding for the NTP was expected from the outset to reduce by 25% each year. However, with this subsidy due to finish this year, schools are now facing the decision to either drop the scheme altogether or fund what they can themselves out of their own budgets. Given the pressures on those budgets, we can expect many schools to either significantly reduce or stop offering tutoring from September. At a time when the attainment gap is widening in a cost of living crisis and school funding is under pressure from all sides, it is far too early to be calling time on a programme that can truly bring educational support directly to the disadvantaged pupils most in need of it.