News

This blog is part of a series looking at challenges and opportunities in education as we come out of the pandemic, based on interviews with a range of experts carried out during 2021.

As with the other parts of the education system covered in this blog series, universities and higher education institutions were hugely disrupted by the pandemic. Significant changes, including moves to online learning, were made in rapid time – a difficult task in large and complex institutions not always known for their speed. With so much change taking place, what can the higher education sector learn from the experience, and what is worth keeping in the aftermath of the pandemic?

Decision making

Because of the pandemic, institutions had to sometimes make changes in days or weeks which would usually take months or years. While hugely challenging, these challenges had, for many of our interviewees, also brought about opportunities.

“Universities had to blow up their existing governing structures to get things off the ground during the pandemic. Some of the transformations we have seen would need to go through many stages of approval internally, including approval from committees who only meet every three months – in the pandemic, it was able to happen overnight, and was quite successful.”

One of our experts also spoke about how this faster decision enabling more junior members of staff, who often spent more time interacting with students directly, to make decisions on the use of resources to best support these students. This was in their view hugely beneficial to universities when navigating the challenges of the pandemic, for example the pivot to home learning. and is something which they thought should be taken forward after the pandemic.

Interviewees reported that some universities were able to speed up mental health appointments in response to an increase in need during the pandemic, and that this showed what could be possible in more normal times.

While many of our interviewees saw a benefit to these changes in ways of working, they were also worried that it would be easy for universities to go back to business as usual after the pandemic, and to lose the agility they had gained.

“Most universities are looking at lessons learnt from the crisis in some way or another, for example, there’s lots of talk around digital and flexible workplace arrangements and working from home. But I’ve heard much less about changing underlying ways of working, such as faster decision making, or empowering staff to make decisions.”

Online learning

Amongst our interviewees, there was widespread praise for the sector’s quick adaptation to online learning, but the process did also present challenges.

Some said they felt students were performing better in assessments when away from campus, whilst others noted increased engagement in lectures; in meetings between students and staff; and in student support services. Interviewees also raised the point that expanding online learning can allow students to study at home if they wish to, whether that be for financial reasons, or the fact that staying at home better suits some learners, for example some of those with disabilities or caring responsibilities.

However, several commentators believed that face to face time shouldn’t reduce with the shift to increased online learning, but should instead be used more effectively. One interviewee highlighted the need for students impacted by the pandemic to have access to face to face provision, saying that –

“After a year of being cooped up and lonely, the last thing you need is 8 hours of in person teaching pre-pandemic turning into 4 hours in person and 4 hours now online.”

Sutton Trust research carried out during the pandemic highlighted some of the challenges of online delivery, with 29% of students put off from doing extra-curricular activities online during the pandemic due to a lack of social interaction, and 24% citing “zoom-fatigue” as a barrier, not wanting to spend more time online after completing lectures and course content virtually.

Some interviewees suggested moving lectures online, but using in person time to connect with peers and lecturers, with networking opportunities like careers fairs remaining on campus. There were also concerns about a loss of more informal conservations between students and university staff if less time was spent on campus.

“Online provision going forward is where I’m torn – on the digital side it has been hugely beneficial being able to connect people more quickly than before. But you do lose something without face to face connections. There are important opportunities to build soft skills in person, especially for disadvantaged students.”

Access to remote learning and the digital divide

As with our experts in in the schools sector, there were concerns amongst interviewees about the continuing digital divide. Our experts were worried that not all students, and especially those from lower income families, would always have the devices or the internet access needed to study remotely.

“At the start of the pandemic, everyone assumed students were all digital natives, that they would all have computers and it would be fine. But what we found was a group of students trying to complete degrees on mobile phones.”

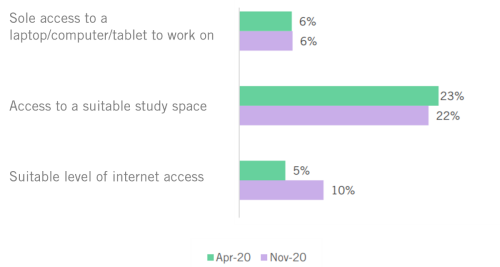

Figure 1: Percentage of students with insufficient access to the resources needed to complete their university work or assessments during the pandemic – November and April 2020

Source: Covid-19 and the university experience, R. Montacute & E. Holt-White (2021) The Sutton Trust https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/covid-19-and-the-university-experience-student-life-pandemic/

Others were worried about access to adequate study space. For students in halls of residence, there were concerns that the spaces had not been designed with the current blended learning model in mind, and would often not have enough space for students. There were also worries for students in houses of multiple occupancy (HMOs) in the private rental sector, where space can be very cramped and provision of very low quality.

“Before the pandemic, we had already abandoned the idea of a shared experience in student accommodation – some students can pay for much better accommodation than others. But for all students, if living at home or living in a fancy student block – you aren’t meant to spend loads of time in them, the spaces students have been living in are not designed to have people in for lots of time, for example multi-occupancy houses where living rooms have been turned into bedrooms now. They all have small rooms. If we are serious about reducing, by stealth or by design, the capacity of campuses and transferring time spent learning and interacting to student’s living spaces – they need to be bigger.”

Improving university IT rooms, creating social learning spaces on as well as off of campus, and revitalising the design of student accommodation were put forward by interviewees as potential solutions to these problems, but many acknowledged that these issues would be difficult to tackle.

Admissions

Interviewees generally felt that there is still not a strong enough push for widening participation in the most selective universities, including the Russell Group. Our experts were also largely in favour of contextual offers, whereby the context of a student is taken into account when making an offer in order to spot potential, with several saying they had become even more significant during Covid.

On admissions during the pandemic specifically, when speaking about last year’s teacher assessed grades, one interviewee said – “Universities need to think carefully about the transition and first year students. They have to be sensitive to lost learning and flex their curriculum to deal with it, there is nervousness around the fact exam results won’t necessarily accurately reflect the level of learning there was or could have been”

Outcomes for contextually admitted students were discussed by interviewees, with several citing research findings that state school students outperform their privately educated peers on average when at university. However, it was also raised that contextually-admitted students may have higher drop-out rates. The interviewee argued that there must therefore be significant support for this group of students once they get to university; it’s not just about getting them in. The transparency of contextual offers was raised as a key consideration. Interviewees felt that currently the system is not always formulated, clear or well-explained.

One criticism of contextual admissions which was raised by some of our experts was that it risked embedding the existing hierarchical nature of higher education in the UK. One interviewee felt that if universities were more similar to one another, it would not matter so much if young people simply attended their local university. Interviewees pointed out that there is a call for employers to broaden the universities from which they recruit, but that there is a risk that contextual admissions are signalling in the opposite direction, and actually perpetuating the hierarchy of HE institutions, rather than seeking to change it.

Another interviewee wanted to see a much greater focus on access at postgraduate level – “As more students get a degree, it’s inevitable it will devalue it, and you will need a mixture of more experience and other qualifications to put yourself ahead. But support available for postgraduate study is far weaker. That will mean students taking on even more debt, and there is not really any drive nationally on widening participation at the postgrad level.” Access to postgraduate education is explored in detail in a recent Sutton Trust report, Inequality in the highest degree?, which finds continuing barriers for those from lower income homes in accessing masters- and PhD- level study.

Higher education post pandemic

Our interviews have highlighted both challenges and opportunities for higher education as we emerge from the pandemic.

Changes like an increase in remote learning and associated flexibility have the chance to transform university for the better, but there are also issues which need to be considered carefully alongside this transformation, especially when it comes to ensuring that young people from lower income families have equal opportunities to benefit.

If universities can manage these transitions, and keep some of the best parts of their pandemic responses, the sector will emerge from the crisis in a stronger position to support all students, including those from lower income homes.

For more information, see our introductory blog, where you will also find links to the whole series.