Press Releases

This year’s GCSE students have had a turbulent time throughout secondary school.

The pandemic and associated school closures started during their year 8, with continuing disruption throughout year 9.

And their GCSE years have been far from a return to normality, with high rates of persistent absences, and the ongoing impact of the cost of living crisis – issues which have all impacted the poorest students the most heavily.

GCSE results in 2023

This year, as with A level exams, Ofqual have aimed to move back to the pre-pandemic grading standard, which required a large fall in grades compared to 2022. The system they put in place does have some protections for overall falls in attainment for the cohort, but cannot take into account individual level learning loss.

Last year, the first where grades moved back towards 2019’s standard, the attainment gap at GCSE between poorer students (those eligible for free school meals) and their better-off peers widening to a level not seen since 2011.

We won’t have an update on the attainment gap for a few more months, but last week gave us some initial data on differences by school type and region. Together, they give a mixed picture of the potential impact of this year’s results on future social mobility.

School type

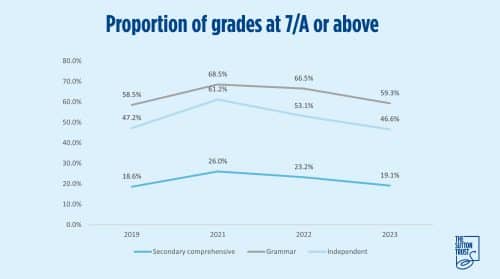

During the pandemic, top results (grade 7/A and above) increased considerably for students at independent schools, hitting a high of 61.2% in 2021, before falling to 53.1% last year. The pandemic also saw a growth in the attainment gap between independent and comprehensive schools, again hitting a high in 2021 at 35.6 percentage points, before falling to 29.9pp in 2022, slightly above the level pre-pandemic (28.6pp).

This year, grades at independent schools have fallen further than at other school types, with top grades reducing to 46.6%, and the gap down to 27.5pp, slightly lower than it was pre-pandemic. While the gap in achievement is still considerable, it does now at least appear that the trend is heading in the right direction.

Results at grammar schools have remained high, coming down less than those of private schools, from a high of 68.5% during the pandemic, to 59.3% this year. The attainment gap between grammars and comprehensive schools also widened during the pandemic, coming back down today to 40.2pp, slightly higher than it was pre-pandemic (39.9pp).

The story has been slightly different when looking at pass rates (those achieving at least a 4/C and above), with the gap actually reducing during the pandemic (22.6pp in 2019, but only 19.4pp in 2022), but this figure has also returned to pre-pandemic levels, now standing at 22pp. A similar pattern was seen between grammars and comprehensives, with the gap now slightly lower than it was pre-pandemic (28.7pp compared to 29.3pp in 2019).

However, when looking at differences between state and independent schools particularly, others have cautioned that trends may at least be partially explained by changes in entries for international GCSEs, which aren’t included in this data, and are more likely to be taken by independent school pupils.

Geography

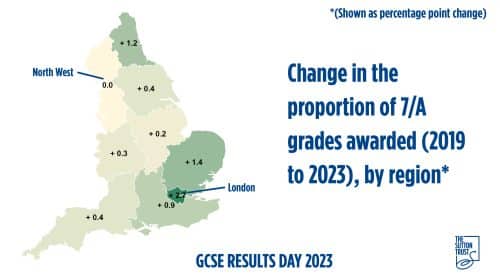

London has continued to move ahead of the rest of England. Looking again at top grades, the largest differences this year compared to 2019 have been in London (where grades have increased by 2.7 percentage points), East of England (up 1.4pp) and the North East (up 1.2pp). Only one region, the North West, did not see an increase on top results, with results here the same as they were pre-pandemic.

And on those achieving a pass (grades 4/C and up), similarly even with a reduction since 2022, there have been increases in several regions compared to 2019, including London (+2.0pp), East of England (+1.5pp) and the North East (1.5pp). Conversely, results stayed the same in the East Midlands, and actually fell (-0.1pp) in the North West.

Despite this growth in both top grades and passes across several regions, we continue to see large disparities in the overall student achievement in different parts of the country, particularly between the North and the South of England.

National reference test

The National Reference Test provides a benchmark for achievement in English and maths that is consistent over years and not subject to policy decisions on grade boundaries.

Last year’s data showed a drop in performance in both subjects compared to pre-pandemic levels, but more pronounced in maths.

This year’s data shows trends in English and maths moving in opposite directions. English grades at both 7 and above and 4 and above have improved since 2022, and are now closer to pre-pandemic levels (2020). However, maths grades have fallen further since 2022, at both Grade 4 and Grade 7.

These results show that, separate to any changes in GCSE results, this cohort have experienced learning loss from the pandemic, something that is likely to continue to impact them into the long term.

Where do we go from here?

The pandemic has clearly had a considerable impact on this year group and is likely to continue to impact on the GCSE attainment gap for years to come, as cohorts in school during the crisis come through to their first national exams.

Government should be looking at greater support for students impacted by the pandemic, as well as doing more to tackle pre-existing inequalities, by putting in place a national strategy to close the attainment gap. A key part of this is a long-term plan with sufficient funding for the National Tutoring Programme, an evidenced backed intervention which has huge potential to help narrow the attainment gap.

For this week’s GCSE students, their schools, colleges, employers and training providers will need to step up to give them continued support as they move onto their next steps, taking into account the impact the pandemic has had on their learning and development. Young people heavily impacted by the crisis have just as much talent and potential as those in previous years, we need to make sure they all have an equal chance to fulfil it.